The Deaths of Migrant Journal –

In hindsight, there is some irony in the care with which we planned the death of Migrant Journal. The group of four designers and researchers we formed to cocreate this publishing platform—Isabel, Christoph, Catarina, and myself—were jumping from short-term contracts to freelance jobs, in no position to plan our professional or financial lives for more than a few weeks at any given time, unable to put any money aside for a 35-year mortgage that has now become the norm, incapable of contributing to one of those hypothetical retirement plans to take effect in half a century or to contract this type of life insurance that ensures wealth in death—or so I hear. Yet Migrant Journal had its lifespan and funeral carefully calibrated. The six-issue publication would see a new “volume” released every six months, like an atomic clockwork, for three years, before expiring its last breath in June 2019. And as I’m writing these lines, we’re on course. Our fifth issue, “Micro Odysseys,” was launched on Monday November 5 at Tate Modern.

Yet, this programmed death is a far cry from any idea of obsolescence—actually it is exactly the opposite. This “time-limited” intellectual project begs the question of life after death, and the immateriality of culture. Can an intellectual and creative time capsule like Migrant Journal continue its intellectual journey beyond then chronicity of its new issues? Can a print-only publication bloom and mature if it does not actively generate “new content” (the phrase is ugly, hence the quotation marks).

But now I wonder: will Brexit kill us first? On 23 June 2016, 15 million British voters, against 13 million, decided to vote in favor of leaving the European Union, threatening the life of Migrant Journal (a truly European and international project, but legally based in the United Kingdom), or at least potentially making it way more difficult, while nurturing its political project, making it even more urgent.

Migrant Journal was cofounded by four migrants, i.e., people who do not live in the country where they were born or for which they hold nationality: Isabel Seiffert and Christoph Miller, of Offshore Studio, are respectively German and Austrian nationals living in Switzerland; Catarina de Almeida Brito, Portuguese via Brussels living in London; and myself, a French national living in London. We’ve now been joined by Michaela Büsse, German in Switzerland, and Dámaso Randulfe, Spanish national living in the United Kingdom.

But the Brexit vote certainly burst a bubble of privilege for people like me, who were born considering Europe as their transnational home with total freedom of movement. Borders, customs checks, and long queues for passports. Brexit forced us to reflect on the materiality of Migrant Journal, as a medium and an intellectual endeavor. Books and ideas live on because they can travel more easily than people; if we’re blocked by borders and passport checks, what remains of Migrant Journal? The walls and imaginary lines we question in this project have never been so alive.

The Materiality of Paper, the Volatility of Culture

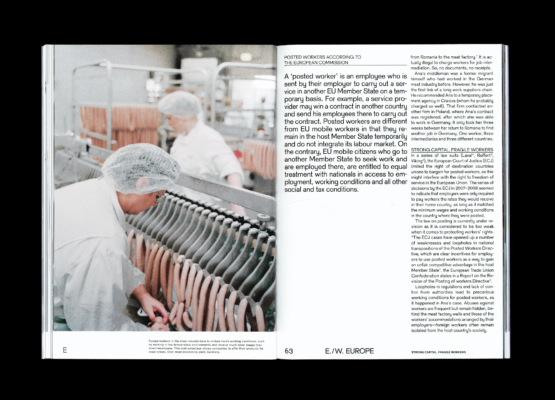

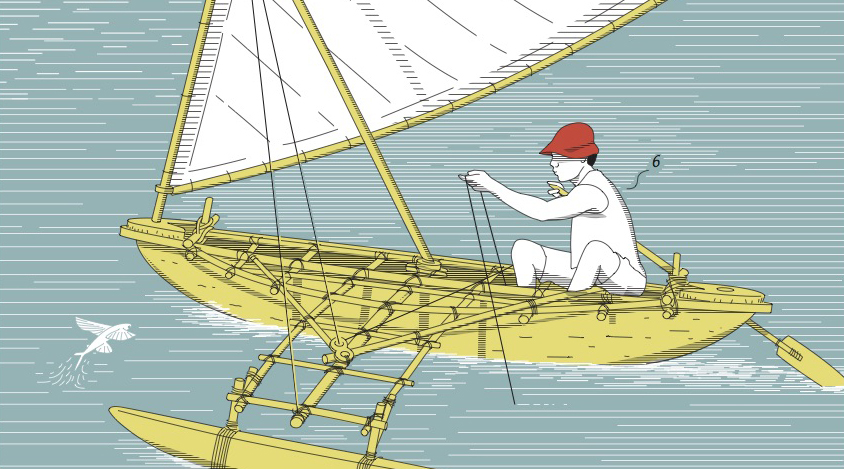

Migrant Journal is a print-only periodical looking at migration in all its forms—people, ideas, goods, finance, culture, birds, seeds—and its impact on space. It is strongly influenced by a critical approach to space and design. It was imagined as a horizontal publication, where editorial and design thinking is/are taking place simultaneously: where form and content are deeply interwoven. Each issue is structured around a theme and a call for proposals: MJ No. 1, “Across Country,” looks at the countryside; MJ No. 2, “Wired Capital,” examines finance and the circulation of goods but also the relationship between capital and information technology; MJ No. 3, “Flowing Grounds,” is interested in everything that’s not on terra firma, i.e., the seas and the skies; MJ No. 4, “Dark Matters,” focuses on the night and obscurity, darkness; MJ No. 5, “Micro Odysseys,” studies the very small, the minute, that is omnipresent in our everyday lives; and our ongoing call for submissions for MJ No. 6, “Foreign Agents,” invites proposals that look at the migration of culture and aesthetics. The publication is multi- and transdisciplinary, with contributions by artists, writers, journalists, photographers, designers, philosophers, geographers, architects, and academics.

Migrant Journal has sold 14,000 copies to date—picturing those 14,000 items dispatched across the world and sitting in bookshelves, cabinets, bookshops, libraries, barbershops, cafés, and offices still baffles me. There is a poetry inherent to the dissemination of materialized knowledge.

An issue of Migrant Journal weighs between 413 and 440 grams (14 1/2 and 15 1/2 ounces)—depending on how many pages it contains. Sending one single copy of Migrant Journal to Europe or North America costs around 6€, for other regions of the world, around 8€ or even 10€. Printing and shipping carry costs that someone has to bear: the reader or the publisher, usually both. In a digitalized global realm, the financial and logistical infrastructure of moving a cultural good from A to B is often overlooked. To print is to confront your desire to reach out to the many with the limitation of physics, and the costs of international mail services.

As a result of physical and social boundaries between Europe and other parts of the world, we sadly have very limited readership in Africa, South America, and Central America, and only a small number of readers in Asia. The map of our “Sessions by country,” which illustrates where those who visit our website migrantjournal.com are located, have one big empty space: the African continent. Over the last few months, we received five visits from Nigeria, 35 from Morocco, and 3,460 from the United States. We are distributed in a few bookshops in Asia (China, Singapore, Taiwan, Hong Kong), but none in Africa; only one in South America (Post Nothing in Bogotá, Colombia), and another one in Central America (Casa Bosques in Mexico City). The majority of our contributors are located and/or come from the “Global North,” once again failing at taking those walls and barriers down to truly engage in a global project. This is partly due to the limits of our social networks, which, despite “globalization,” remain limited by where we live and who we hang out with. This is also due to the materiality of a project like ours: the 413–440 grams of Migrant Journal.

In our second issue, “Wired Capital,” we interviewed the sociologist Saskia Sassen on the notion of liquidity versus materiality. Sassen has been studying the spatial dynamics of globalization and their impact on space for decades, coining concepts such as the now-ubiquitous “Global Cities.” This capacity of the market to transform real estate into liquidity, traveling the world as digital abstraction, is one of the conundrums we’ve been studying with fascination throughout the project. The limits and opportunities of space’s materiality echo the 180 x 245 mm (7 x 9 1/2 in.) trim size of Migrant Journal.

Print travels, but not as fast as the ideas it tries to identify, understand, and enhance. Therefore, our ambition to disseminate Migrant Journal’s project as a materialized object and as an intellectual endeavor, to widen our community of readers and contributors, and to question the notion of migration and challenge the negative political discourse utilizing it lives on.