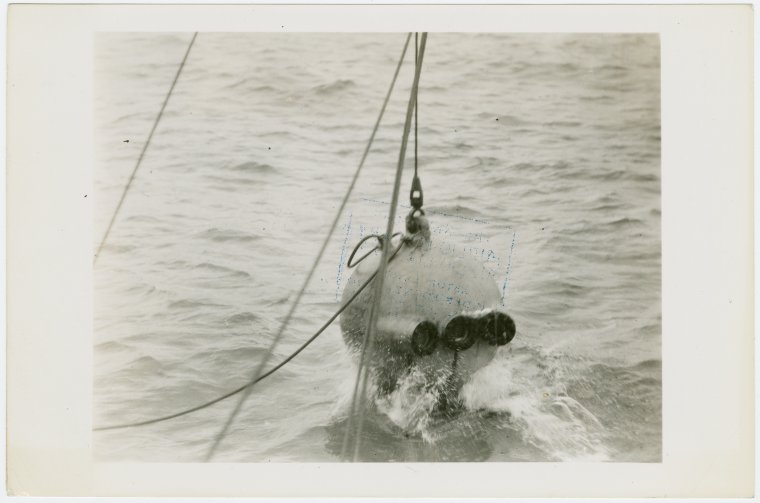

EDITOR’S NOTE: In 1930, American naturalist and marine biologist William Beebe together with engineer Otis Barton and scientist Gloria Hollister set out to explore the marine environment down to a record half mile depth with the help of a submersible capsule called the bathysphere, marking the first human forays into the deep ocean. The following text is a fictionalized piece by Brad Fox in response to a question from science historian Katherine McLeod. It forms a work-in-progress based around the expedition logs of the bathysphere dives that took place off the island of Nonsuch, in the Bermuda Archipelago, between 1930 and 1934.

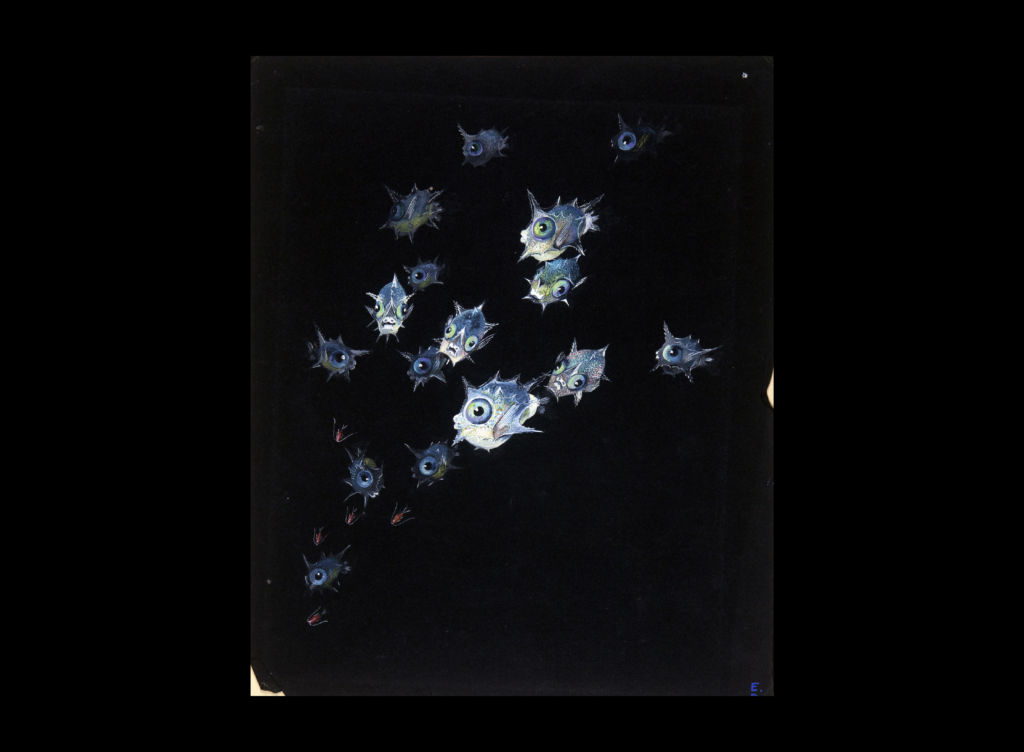

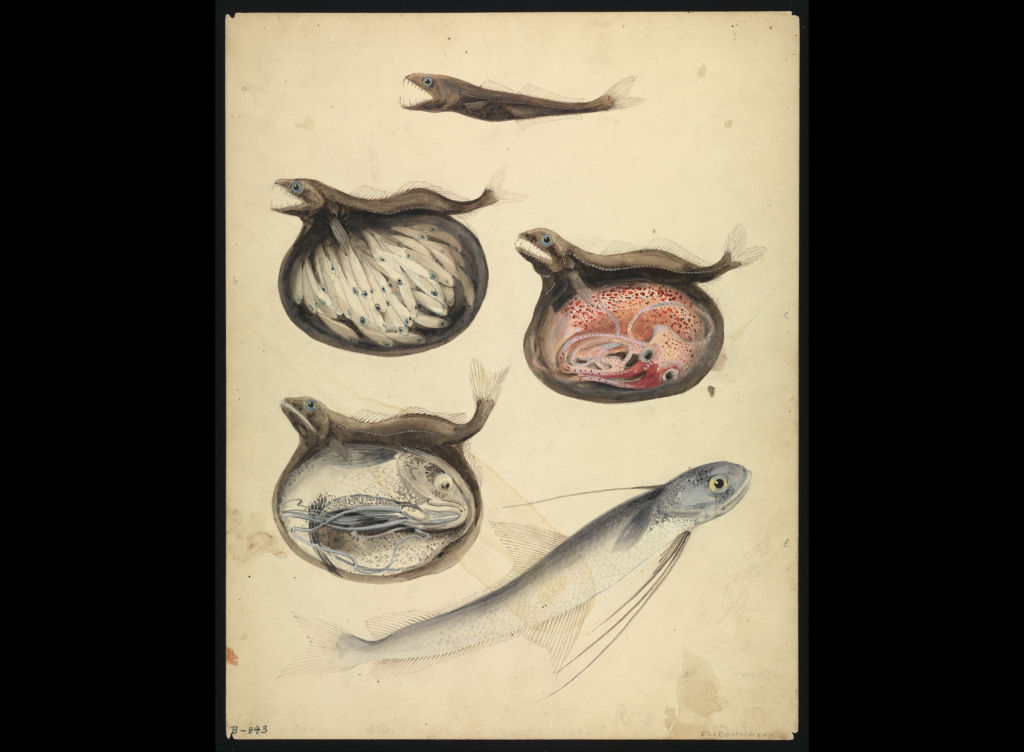

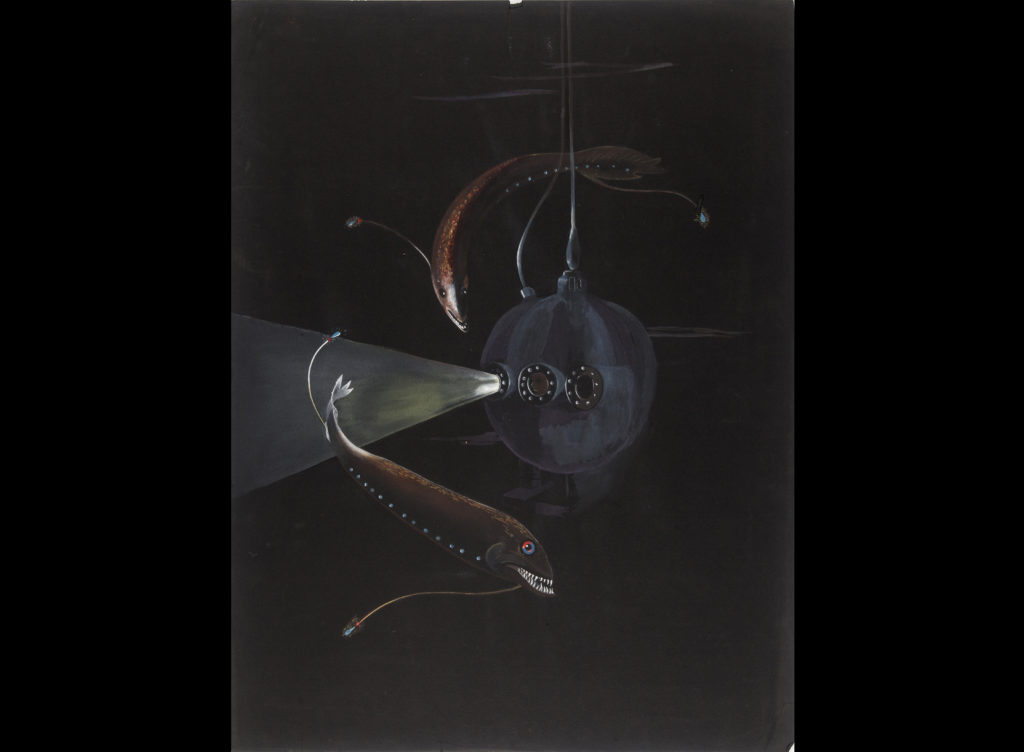

There out of the darkness of the deep appeared a long, slender, glowing shape—Beebe knew it was a kind of siphonophore. It was enormous—some twenty yards from end to end. It appeared to be a pale magenta color, but that seemed impossible given the spectral restriction down here. It had no head or legs but varied in texture and shape, a complex form with tendrils extending from its sides and gently but rapidly flagellating the water.

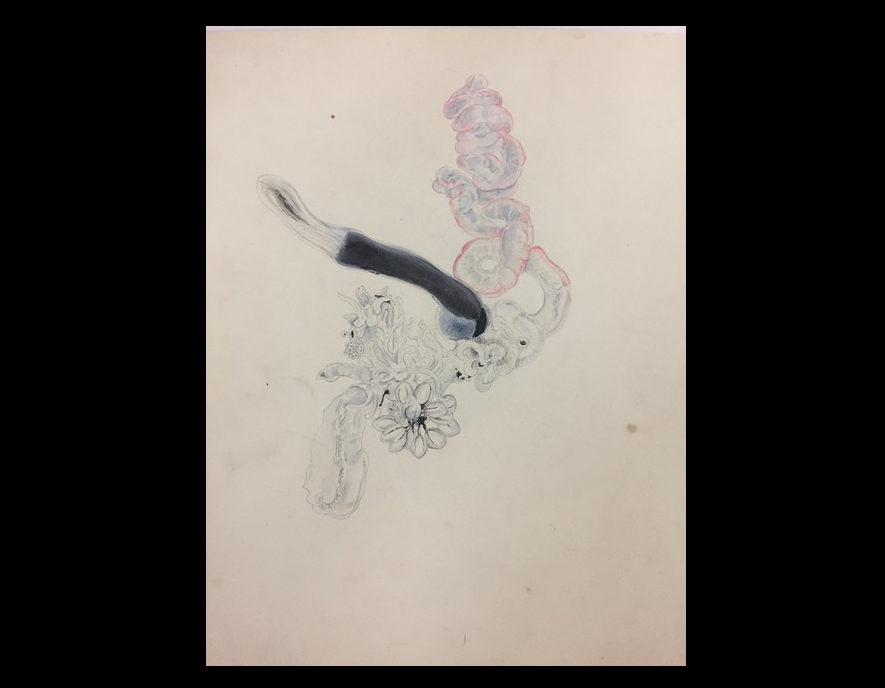

A siphonophore appears to be a single organism, but it’s not. It’s a colony of smaller animals—polyps and other beings called zooids. It’s a city adrift in the ocean, an undersea New York whose citizens cooperate closely to keep the bustling society harmoniously alive.

The citizens share a common ancestor that once emerged from a fertilized egg, but now they grow and clone themselves and attach their offspring to their own bodies. These new bodies are genetically identical to their parent but develop differently, acquiring finely honed skills. There is no central brain—each creature has an independent nervous system, but they share a circulatory system. This frees the small bodies to pursue whatever they might devote themselves to. Some provide protection, some are responsible for eating, for reproduction, or for producing colorful glowing light. Some absorb water and squirt it back out, propelling the siphonophore through the water. Some absorb air or fill with gas to regulate buoyancy. The nectophoric jellies that propel the siphonophore can’t eat, and the polyps that eat can’t swim. They depend on each other, working together as one.

Some of the animals grow dangling limbs at the perimeter, and these can produce powerful neurotoxins that stun small shrimp or other creatures for food. The limb then enwraps the shrimp and digests it, distributing its energy throughout the city.

Siphonophores can grow to be over a hundred feet long. Most are very slender, seemingly composed of a transparent, gelatinous material like jellyfish. Some have dark orange or red digestive systems that can be seen inside their transparent tissues. Some turn green or blue when disturbed. They are extremely fragile, and break into pieces at the slightest touch. But in their highly organized state they are the longest creatures on earth, if they can be considered a single creature at all.

Humans bodies, too, contain multitudes—not only the individual cells that make up our tissues and organs, but the bacteria and other animals that live within us. To them we are an ecosystem. Siphonophores are as complicated as humans, with organs performing different tasks. To the individuals that compose them, the integrity of the body is a social impulse that binds them in cooperation.

Siphonophores call out to us to rethink our individuality, to consider our epidermis as only one way to measure the extent of our bodies. To them, our furious competition, our backstabbing and fights over resources, is nonsense. Better we work together, getting closer and closer, more finely attuned to each other’s needs until we are indistinguishable. Then we might draw our boundaries differently.

When some Buddhist monks meditate, key parts of their brains quiet and go still. One is the part that locates us in space—we bump into a table, and it knows that is one place where our bodies stop. This boundary is emphasized as we bump into things again and again, come into contact, feel and move against things and against each other. But this division is only a habit of mind. There is nothing essential about it. When that part of the brain stills, we no longer distinguish between us and not us.

At such a moment, let loose from the limits of the body, as we float in a greater unity, the siphonophore might inject us with powerful neurotoxins, to remind us that there is no answer.