This text was originally published in the first issue of the Journal of Design and Science on January 13, 2016.

To every age, a relic: a loom, an automobile, the PC, a 3D printer. L’Encyclopédie[i] was its period’s signpost, cataloguing and concretizing the boundaries between the disciplines, which emerged from the “long eighteenth century” of the Enlightenment. For the next quarter of a millennium, we remained indoctrinated to the shibboleths of this relic, operating within discrete silos-of-thought. At the dawn of the new millennium, the meme “antidisciplinary” appeared, yanking us out of Aristotle’s shadow and into a new ‘Age of Entanglement.’2 3

This essay proposes a map for four domains of creative exploration—Science, Engineering, Design and Art—in an attempt to represent the antidisciplinary hypothesis: that knowledge can no longer be ascribed to, or produced within, disciplinary boundaries, but is entirely entangled. The goal is to establish a tentative, yet holistic, cartography of the interrelation between these domains, where one realm can incite (r)evolution inside another; and where a single individual or project can reside in multiple dominions. Mostly, this is an invitation to question and to amend what is being proposed.

Maeda finds Gold

All roads lead to the “Bermuda Quadrilateral.”4 In 2007, John Maeda proposed a diagram under this name, based on the “Rich Gold matrix.”5 The map—a rectangular plot—was parceled into four quadrants, each devoted to a unique view by which to read, and act upon, the world: Science, Engineering, Design and Art. According to Maeda, to each plot a designated mission: to Science, exploration; to Engineering, invention; to Design, communication; to Art, expression. Describing the four “hats” of creativity, Rich Gold had originally drawn the matrix-as-cartoon to communicate four discrete embodiments of creativity and innovation. Mark your mindset, conquer its little acre, and settle in. Gold’s view represents four ways-of-being that are distinctly different from one another, separated by clear intellectual boundaries and mental dispositions. Like the Four Humors, each is regarded as its own substance, to each its content and its countenance. Stated differently, if you’re a citizen in one, you’re a tourist in another.

But how can we become constant travelers within a border-free, and lingo-legible ‘intellectual Pangea?’ How can we traverse a cerebral supercontinent, where the analog of world citizenship governs our identity as thinking—and creating—beings? How can we navigate an atlas that is charted not for four hats, but for one pair of shoes, and with which we can—including some luck and a quantum leap-of-faith—inhabit multiple places at once? Can a scientist invent better solutions than an engineer? Is an artist’s mindset really all that different from a scientist’s? Are they simply two ways of operating in the world that are complementary and intertwined? Or, when practicing art, is perhaps what truly counts less the art form and more one’s (way of) being? Ultimately: is there a way to understand the culture of making which transcends a two-dimensional Euclidean geometry—four plots to match four hats—to a more holistic, integrative and globe-like approach?

Caving

In his recent film, Particle Fever (2014), Mark Levinson documents the first round of experiments at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), investigating the origins of matter. The film opens with the initial firings of the LHC, designed to recreate the conditions associated with the Big Bang. It closes with prehistoric cave paintings, and an intriguing assertion by Savas Dimopoulos on the connection between Art and Science: “The things that are least important for our survival are the very things that make us human.” Both Art and Science can be understood as human needs to express the world around us. Both require suspension of disbelief, offering speculations about our physical and immaterial reality prior to proof. And both—as has been the case since the painting of the Chauvet Cave some 40,000 years ago—have no rules and no boundaries. The artists who produced these paintings did so in order to first face, then make sense of, their reality. We do Science with precisely the same motivation. Similarly nebulous are the boundaries between Design and both Art and Engineering. Design, in its critical embodiment (Critical Design), operates through speculation, devising unforeseen strategies that challenge preconceived assumptions about how we use, and live within, the built environment. In its affirmative embodiment (Affirmative Design), Design operates by offering practical, and often utilitarian, solutions that can be rapidly deployed. The former carries the mentality of Art, while the borders between the latter and Engineering are at best difficult to parse. Similar vagaries exist, too, between Science/Design, Engineering/Art, and Science/Engineering. It is likely to assume that if what you are designing carries meaning and relevance, you are not operating within a single, distinct domain.

How can we re-occupy the four corners of the “Bermuda Quadrilateral” as transitory embodiments of creativity and innovation? Better yet, how can we travel them, or even co-exist within them, in a way that is at once meaningful and productive? Can operating within one domain generate a kind of ‘creative energy’ that enables the easy transition to another?

Creative Energy (CreATP)

The Krebs Cycle is a metabolic pathway made up of chemical reactions. One of the earliest established components of cellular metabolism, all breathing organisms could not exist without it. Its outcome, through the oxidation of nutrients, is the production of chemical energy, carried throughout the cell in the form of Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP). ATP can therefore be considered a molecular unit of currency for energy transfer. The Krebs Cycle is akin to a metabolic clock that first generates, then consumes, then regenerates currency in the form of ATP over time. Crudely expressed: good metabolism will make you constantly rich. By the same token, can intellectual digestion—the kind that demands you shift views and perspectives—make you constantly intellectually rich?

The Krebs Cycle of Creativity (KCC) is a map that describes the perpetuation of creative energy (creative ATP or ‘CreATP’), analogous to the Krebs Cycle proper. In this analogy, the four modalities of human creativity—Science, Engineering, Design and Art—replace the Krebs Cycle’s carbon compounds. Each of the modalities (or ‘compounds‘) produces ‘currency’ by transforming into another:

The role of Science is to explain and predict the world around us; it ‘converts’ information into knowledge. The role of Engineering is to apply scientific knowledge to the development of solutions for empirical problems; it ‘converts’ knowledge into utility. The role of Design is to produce embodiments of solutions that maximize function and augment human experience; it ‘converts’ utility into behavior. The role of Art is to question human behavior and create awareness of the world around us; it ‘converts’ behavior into new perceptions of information, re-presenting the data that initiated the KCC in Science. At this ‘Cinderella moment’—when the hands of the KCC strike midnight—new perception inspires new scientific exploration. For example, in As Slow as Possible, John Cage transports the listener into a state where space and time are stretched, offering a personal interpretation of time dilation and questioning the nature of space-time itself.

The KCC is designed as a circle with the four modalities of creativity preserved in their original location from the “Rich Gold matrix.” As you transition from one into the other, you generate and spend currency in the form of intellectual energy, or CreATP. Science produces knowledge that is used by engineers. Engineering produces utility that is used by designers. Designers produce changes in behavior that are perceived by artists. Art produces new perceptions of the world, thereby granting access to new information in and about it, and inspiring new scientific inquiry. As in the cumulative Aramaic song, Chad Gadya, there is repetition, continuity and change. Some content is generated, other content is consumed, some is released and new content is formed.

The Clock, the Microscope, the Compass and the Gyroscope

As a speculative map, the KCC is intentionally abstract. In hopes of eliciting debate and revision, its many meanings can be read through a multiplicity of lenses.

KCC as Clock

The KCC can be read as a clock like the Krebs Cycle itself. But unlike the Krebs Cycle, the CreATP pathway is bidirectional. In this clock, direction can be reversed. Time can also stand still (by remaining in the same location on the circle), it can ‘bend’ (by introducing geometrical changes, e.g. from a circle to an ellipse), or it can be foreshortened (by introducing topological changes, e.g. from a circle to a figure eight or a spiral). Furthermore, if you generate excess energy, you can skip domains—from Science to Design, bypassing Engineering—and thereby ‘time travel.’ We get boosts of CreATP for free when we are good at what we do, when we excel in integration. Good Design, for example, is good exploration: it questions certain belief systems—physical and immaterial—about the world. Then it releases some embodiments of these speculations into the world, contributing to the build-up of what we know as culture. If done well, good Design can establish new basic Science without going through Art. By example, Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes (“buckyballs”) helped scientists visualize the molecule with the formula C60, whose related class of molecules were named “fullerenes.”

KCC as Microscope

The KCC, in its current form, does not yet express transitions in physical scale. But, of course, you can consider the four domains as four objective lenses of an imaginary microscope through which to view, and act upon, the world. The way we view our environment, and interact within it, is ultimately dependent on the lens through which we choose to see it. Choosing is no innocent act. A material scientist will generally explore the physical composition of matter through the lens of properties. A biologist, however, looks at the world not through the lens of properties, but rather through the lens of function. Both live in the same reality, but experience it altogether differently, and therefore act upon it in a singular way. If they could see both views simultaneously, they would link properties and behaviors.

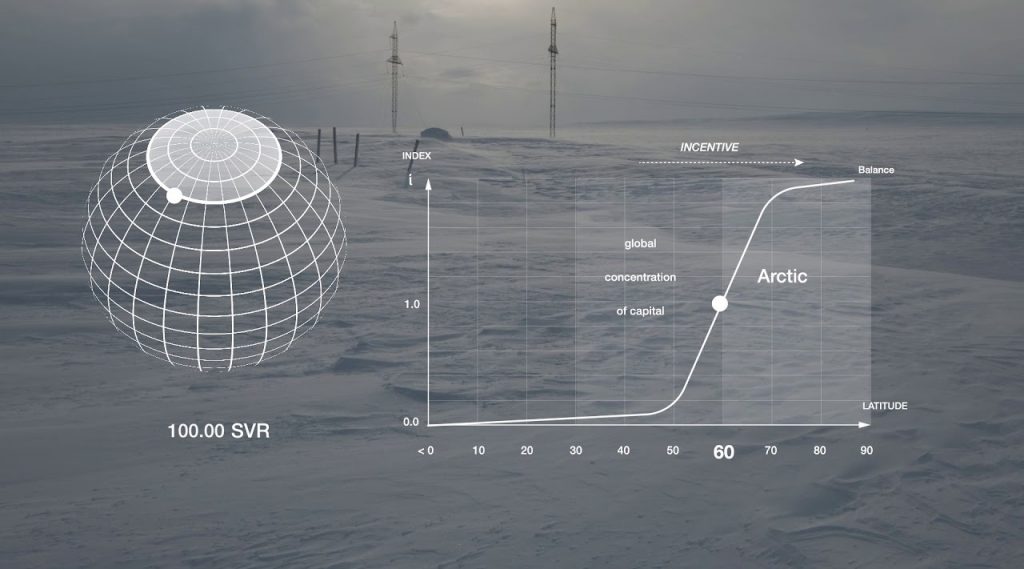

KCC as Compass

The KCC can be read as a compass rose, north-to-south and east-to-west. The north-to-south axis leads from sky to earth: from ‘information’ produced by Science and Art in the hemisphere of ‘perception,’ to ‘utility’ produced by Design and Engineering in the hemisphere of ‘production.’ The farther north, the more theoretical (or philosophical) the regime. The farther south, the more applied (or economic) the regime. The north marks the climax of human exploration into the unknown. The south marks the products and outcomes associated with new creative solutions and deployments based on exploration. The east-to-west axis leads from nature to culture: from ‘knowledge’ produced by Science and Engineering in the hemisphere of ‘nature,’ to ‘behaviors’ produced by Art and Design in the hemisphere of ‘culture.’ Along this axis, one travels from understanding—describing and predicting phenomena within the physical world—to creating new ways of using and experiencing it.

KCC as Gyroscope

Most provocatively, the KCC can be understood as a plan-projection of a gyroscope, measuring or maintaining creative orientation. This analogy imagines a three-dimensional globe transcending ‘flatland,’ where at the very top(s)—the poles of the diagram—all modalities collide into one, big nebula. A Big Bang where all of this actually begins. Complete entanglement.

Holes and Hacks

As with any speculative proposition, particularly when expressed graphically, there are many intellectual holes and cracks.

From Art to Science: a Cinderella Moment

Some claim—and even tittle-tattle the point—that the passage from Art to Science is far-fetched at best, and forced at worst. After all, Picasso and Einstein didn’t know each other (the myth of an impromptu meeting in 1904 at Montmartre’s Le Lapin Agile aside). But does it matter? Both questioned the relationship between space and time, arriving at expressions speculating on their relationship in deep and meaningful ways. Both were archetypes of Modernism, co-existing in an age that questioned the culture of nature…and the nature of culture. Granted, my determination to posit the completed circle—to assert the continuity of the KCC—may be seen as naïve, or even sophomoric. Please assume the former, and suspend disbelief. After all, only through faith (will) we leap. That is to say: the ability to create sufficient leverage to leap from Art to Science is the ultimate force multiplier. It’s where potential energy is converted to kinetic energy, a posse ad esse.

Culture is Nature is Culture

The nature-culture divide is every anthropologist’s bread-and-butter. And the question whether these two entities can be perceived, expressed and acted upon in coalescence carries tension in the KCC’s extrapolated poles. If “nature” is described as “anything that supports life,”6 and if life “cannot be sustained without culture,”7 the two belief systems collapse into singularity. In this singularity, Nature claims the infrastructure of civilization and, equally so, culture now enables the design of Nature herself.

Global Citizenship at the Cost of Intellectual Vernacular

Is intellectual flexibility more worthy than it is profitable? Is global intellectual citizenship a road to perdition? Might simultaneously inhabiting all four domains, or all the silos of enlightenment, entail a loss in disciplinary expertise and research proficiency? Perhaps. Still, you can’t have one without the other: central (disciplinary) vision will get you far, but peripheral (antidisciplinary) vision will get you farther. So while the ability to occupy all four domains simultaneously requires the kind of expertise that sacrifices expertise, it is a sine qua non for a worthy spin.

Antonelli gets ‘Knotty’

A mathematical knot is not what you think. It is not the kind of knot you would use to yoke your shoes or tie a tie. In knot theory, knots are closed loops: they have no ends at which they can be unknotted. It is this very concept that inspired Paola Antonelli to coin the term “Knotty Objects.”8

So what is a Knotty Object?

One can perceive the world as a singularity, i.e., top down through the lens of a particular profession or plot on the “Rich Gold matrix.” But one can also view the world bottom up, object first. Knotty objects are bigger than the sum of their parts. Viewing them fuses multiple perspectives, thereby generating an expanded, more profound, vision of the world. Knotty objects are so knotty that one can no longer disentangle the disciplines or the disciplinary knowledge that contributed to their creation. If in the Age of Entanglement, we understand objects from a manifold of vantages, Knotty Objects force awareness of their condition through a multivalent approach.

During the Knotty Objects summit at the MIT Media Lab (July 2015), Paola Antonelli, Kevin Slavin and I focused on four knotty objects-as-archetypes: a phone, a brick, a bitcoin and a steak. Each posed a particular context for their knotting: communication, the built environment, commerce and gastronomy. But each also begged to be explored through many realms.

Take the steak for example. Its ‘design’—whether it is prepared using the animal as source, or is produced from scratch in a lab—embodies a difficult assortment of technical skill and moral contradiction. While bullfighting beef is ironically considered the most ecological meat in the world, its synthetic equivalent is just as ethically troubling: engineering in vitro meat requires market-driven environmental sacrifices that are just as Homeric as the killing of a sacred bull. Whichever way you look at it, there is no escaping guilt. In this knotty universe, we are still cavemen, controlled by our pre-established moral code and views.

The creation of knotty objects is just as knotty. In fact, the techniques to create them, as well as their ultimate physical expression, are intellectual mirror images of each other: the process reflects the knottiness of their related products. Bluntly, a knotty creator must simultaneously occupy all four domains of the KCC, and bring together insights that are as profoundly scientific as they are artistically insightful.

What is so special about these objects is that their creation—their science, their engineering, their design and their projected location in culture—is not a discrete process; it is nonlinear and cannot be unknotted. When it is considered successful, a knotty object has the power not only to question the way we live, but also to change material practice, to question manufacturing protocols and to completely redefine social constructs. This is a very exciting time for creators of the built environment, a time when the disciplines are knotted within contexts that are at once technologically savvy and culturally sensitive. The knot then becomes the ultimate form of entanglement.

Ito’s Pangea

Since the Age of Enlightenment, the realms of human exploration and expression have been coddled into silos that are self-reliant and often self-referential, both in means and in mindset. But if you can smash protons down a seventeen-mile straw at nearly the speed of light, you’ve earned the right to question the category of gravity. Theoretical physics alone just isn’t enough: it’s an entangled proposition to a truly BIG question, spawned by an entangled state (literally and metaphorically).

“Quantum entanglement” denotes the moment a few or more particles interrelate such that the quantum state of any particle cannot be described alone, only all the particles en masse. If Enlightenment was the salad, Entanglement is the soup. In the Age of Entanglement it becomes impossible to discern one ingredient from another. Taxonomies are defunct; disciplinary walls dissolve. At the extrapolated summit of the KCC as Gyroscope, all silos coalesce (back) into the Pangea of information.

Due to the boon of new fabrication technologies, the scales of synthesis are approaching the already micro scales of analysis, and ‘writing’ the world is thereby becoming as granular as ‘reading’ it. Consider for example the transition of information from an MRI scan to a 3D print in the production of a prosthetic limb with graded properties that match and respond to a particular person’s physiology. Or a wearable micro-biome, designed at a scale that can filter your gut. Just like the cave painters, it is through creative expression that we can re-enter (or re-read) the same view from a different perspective. Communication protocols between and across such perspectives become explicit because, as in the Krebs Cycle, synthesis and degradation are interchangeable. The instant when units of work and units of perception coalesce becomes a thrilling creative moment9 for the free souls and the free soloists in the Age of Entanglement.

The MIT Media Lab — ‘Ito’s Pangea,’ or the ‘Negroponte supercontinent’ — can entangle precisely because it makes the stuff that makes the KCC spin: media. And I don’t mean news, or electronics, or digital media, not even social media. But that which possesses one world: “each hath one, and is one.”10

Acknowledgements

The phrase “Age of Entanglement” is attributed to my good friend and colleague Danny Hillis, who has explored similar phrasing in.11 12

1. The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d’Alembert

2. Danny Hillis, “The Age of Digital Entanglement,” Scientific American. Vol. 303. (2010), p. 93

3. John Brockman, “The Dawn of the Entanglement,” Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think?: The Net’s Impact on Our Minds and Future (Edge Question Series) (New York:Harper Perennial 2011)

4. Thoughts on Graphic Design

5. Design_at_the_edge and Rich Gold, John Maeda, The Plenitude (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press 2007)

6. José Barreiro, Thinking in Indian. A John Mohawk Reader (Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing 2010)

7. Dennis Dutton, The Art Instinct: Beauty, Pleasure, and Human Evolution (New York: Bloomsbury Press 2010)

8. Reference Knotty Objects Summit at the MIT Media Lab, led by Paola Antonelli, Kevin Slavin and Neri Oxman

9. Jeanne Shapiro Bamberger, Developing Musical Intuitions: A Project-Based Introduction to Making and Understanding Music (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press 1999)

10. John Donne, “The Good-Morrow,” Songs and Sonnets, 1633

11. Danny Hillis, “The Age of Digital Entanglement,” Scientific American. Vol. 303. (2010), p. 93

12. John Brockman, “The Dawn of the Entanglement,” Is the Internet Changing the Way You Think?: The Net’s Impact on Our Minds and Future (Edge Question Series) (New York:Harper Perennial 2011)