Gillo Dorfles was born in Trieste on April 12, 1910. The cultural pluralism of the port city, in which Jewish, Austrian, Slavic, and Italian groups coexisted peacefully, marked his life and multifaceted activities. He was an artist, a critic, a professor of aesthetics, and an active member of Italian cultural life for more than eighty years. His research on contemporary art, which opened the field to considerations of anthropology, linguistics, and media studies, was characterized by his strong belief in the civil function of art.

He died in Milan on March 2, 2018; he was 107 years old. We are very honored to have had the chance to hear his opinions about design, nature, and humanity’s relationship to the environment. This interview, from January 21, 2018 in Milan, is previously unpublished; the voice that reaches us here is the last testimony of his vivacity and intellectual independence. Aldo Colonetti is a philosopher as well as a historian and theorist of art, design, and architecture. He is a pupil of Gillo Dorfles.

Translated from Italian by Simon Turner. Original text below.

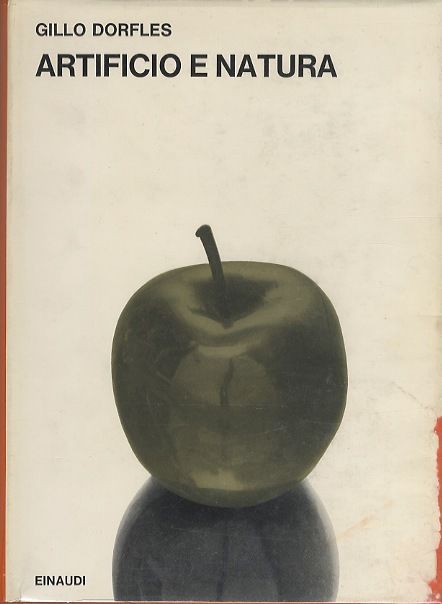

Aldo Colonetti: On the one hand, Broken Nature points to a problem, and on the other, it aims to offer a new approach to design. As Paola Antonelli, curator of the XXII Triennale, puts it: “Ethics and aesthetics can live together and prosper. In good contemporary design, a strong belief system does not lead to aesthetic or sensual penitence.” At the center is nature, viewed as “the best creator, engineer, and maker.” Starting from this charged and dialectical relationship between man and nature, intention and will, utopia and practical ability to design, dear Gillo, I’d like to revisit a series of reflections from the introduction to one of your fundamental essays, Artificio e natura (artifice and nature), originally published in 1968.1 This groundbreaking text was one of the first contributions to tackle this dichotomy, especially by establishing a baseline of philosophical thought. Already a few years earlier, in another book of yours, Nuovi riti, nuovi miti (new rites, new myths),2 you quoted a famous phrase from Hegel’s Aesthetics: “Man duplicates himself.”3 Would it be fair to consider this as a starting point in addressing issues that have roots dating back to the dawn of time, in the relationship between nature and artifice?

Gillo Dorfles: Certainly, even though we need to ask ourselves how we should interpret Hegel’s famous phrase today. To be precise, it says: “Things in nature are only immediate and single, while man as spirit duplicates himself, in that (i) he is as things in nature are, but (ii) he is just as much for himself.” In other words, humans exist for themselves as objects, but at the same time they are able to create other objects that are transformations of nature. These do not already exist in nature but are “objectualizations” of something, and this is what leads to the need to design, to the incessant development of design and production, and to a system of “things” that increasingly become protagonists, turning from “objects” to “subjects.” We need to understand that a “broken nature” is not only the result of a particular economic system: it is part of the human nature—and it is based on this realization that the practice of design needs to be reformed. This means inventing from scratch—beyond all restraints and with regard to all previous models—an infinite series of objects and products that gradually acquire an autonomy of their own. It means moving away from the language of nature, and indeed often transforming nature as though it were an artifice, and itself a product of humankind. Here we need to reflect in order to recompose, even if only partially, a nature that is already broken; a nature that is alienated because we see it as always modifiable, whereas a natural condition has its own “constructive” autonomy and its own laws.

AC: I’d like to discuss this idea, where you stress how central this figure of human as a designer is. This preeminence derives from thinking one is totally independent from one’s context, as though “pure invention” were a sort of force of nature that acts even against nature itself, as we see every day. This leads to a precarious balance between our species and the natural state. This role of human as the “absolute creator,” a dominus that wants to be both nature and artifice, appears to have been acritically adopted by the discipline of design. I’d also add that in all other creative fields that have to do with housing systems, nature appears to be withdrawing in response to this attitude. Where is the ultimate rationale for this sort of dominion over the world?

GD: As we were saying, the tendency of humanity to take on this sort of dominion over the world has always existed. It is mainly in recent decades, however, with the development of new technologies, that we see the worrying phenomena to which I have devoted a series of analyses. They all lead back to a particular condition of humans today, that of the ultimate creator. This notion has spread from the traditional to the creative fields, from our houses to the cities we live in, the transport we take to work, and the way we communicate, all the way to the creation of an artificial consciousness. Our entire environment has already been totally transformed by technologies. Apart from all the immense material benefits that they’ve given humanity, they also tip the balance between man and nature. They set off a series of negative effects, where development exploits natural capital, simply transferring it elsewhere. Instead of an ideological announcement of simplification to serve the nature of humankind, we have the concept of horror pleni—the absence of a gap between one phenomenon and another, which makes it impossible to distinguish between them, making everything appear uniform and equal, and leading to an excess in useless mass-produced objects.4 Today, we also have facts that appear to be true but are actually no more than “fake news”; this basically indicates a false knowledge of the world.5 Here, too, the multiplication of visual languages and systems of representation, coupled with their instant accessibility, causes problems of a pathological nature concerning knowledge of self. It also fills our spaces with an infinite series of intermediations between us and the world, and between nature and artifice, making it difficult for us to direct our choices.

AC: It is, however, possible to find a new balance in which design, for example, is the expression of an organic vision of nature, making better use of materials so that they are not depleted, but also making better use of the forces of nature in general. At the center of all this, I believe in the contemporary relevance of the work of a great philosopher, Edmund Husserl, particularly as reread and interpreted by a dear friend, Enzo Paci, who was the cofounder in 1954 of the Compasso d’Oro—the most prestigious international prize for industrial design—together with you, Augusto Morello, Gio Ponti, and Marco Zanuso. This is what Paci wrote in 1967 about the relationship between science, technology, and manufacturing development: “If science and technology admit no reality other than that of physicalistic things, if science forgets cogito, man, and makes him physicalistic and alienating, then science loses its own basis in cogito, forgetting its own function for men and the telos for humanity.”6 Is contemporary design still able to put this type of telos at its center?

GD: It certainly is possible, and Paci was right, but a few things should not be forgotten. The first is to ensure that art and design communicate with each other, but without trespassing on each other’s fields, for otherwise the multiplication of objects will be relentless and never-ending. We must never forget the originality of our own design work, avoiding useless imitation and self-referential replication. Multiplying is positive, but only when it preserves the originality that is inherent in the fact that it is our nature to create incessantly. It is impossible to go back, as though there were a sort of Garden of Eden of design: we are part of history and we must act upon history. This means that, to improve the current situation, we need to “redeem the unnatural,” transforming artificial events into natural or “naturalized” events, through our knowledge and willpower. It means considering nature not only in its wildest state, but especially in all its new mechanized, electronically integrated, and internetized forms. The artificial constructions of the human species need to be gradually rectified, undergoing a process of naturalization that can only come from a new creative and symbolic approach. It is necessary to bear in mind and keep an eye on all research and inventions involving new materials, and new production processes that take into consideration both the consumption of energy and the waste of resources. But we must never abandon our creative freedom, with greater autonomy inspired by knowledge, and less heteronomy that leads only to repetition and imitation of what already exists. We shall always need “new objects” that are still able to talk the language of a real future. One that is recognizable, and also able to interact with the cognitive and interpretative autonomy inherent in all people, whatever their language, religion, or economic status. Every person is a free subject, and this is our fundamental natural dimension. Gradually restoring it means acting in the spirit of a nature that is no longer “broken.”

1 Gillo Dorfles, Artificio e natura (Turin: G. Einaudi, 1968).

2 Gillo Dorfles, Nuovi riti, nuovi miti (Turin: G. Einaudi, 1965).

3 G. W. F. Hegel, Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics, ed. Michael Inwood, trans. Bernard Bosanquet (London: Penguin UK, 1993).

4 Gillo Dorfles, Horror pleni (Rome: Castelvecchi, 2008).

5 Gillo Dorfles, Fatti e fattoidi (Rome: Castelvecchi, 1997).

6 Enzo Paci, “Per un’interpretazione della natura materiale in Husserl,” Aut Aut 100 (1967).

Original Italian text

Dialogo tra Gillo Dorfles e Aldo Colonetti intorno al tema della XXII Esposizione Internazionale della Triennale di Milano, “Broken Nature: Design Takes on Human Survival”

Aldo Colonetti: Broken Nature indica da un lato un problema e dall’altro intende proporre una nuova prospettiva progettuale in cui, come scrive Paola Antonelli, curatrice della XXII Triennale, “etica ed estetica possono convivere e prosperare, con esempi di design a tutti i livelli il cui spessore morale non comporta una mortificazione estetica e sensuale”. Al centro, una natura intesa come il “migliore creatore, ingegnere e costruttore”.

A partire da questa complessa e dialettica relazione tra essere umano e natura, intenzione e volontà, utopia e possibilità concreta di “progettare”, andrei a rileggere, caro Gillo, una serie di tue riflessioni che introducono un tuo testo fondamentale, Artificio e natura,1 pubblicato nel lontano 1968. Il saggio, uno dei primi a livello internazionale, affronta questa “dicotomia”, non solo alla luce dei risultati, ma soprattutto partendo da una sorta di “grado zero” della riflessione filosofica. Già alcuni anni prima, in un altro tuo libro, Nuovi riti, nuovi miti,2 citavi una famosa frase di Hegel, ”l’uomo si raddoppia”, presente nella sua Estetica.3 Si potrebbe affermare che è necessario ripartire da qui, per affrontare un tema che ha le sue radici già nella relazione, all’inizio dei tempi, tra natura e artificio?

Gillo Dorfles: Certamente, anche se è necessario chiedersi com’è possibile intendere oggi questa famosa riflessione di Hegel che esattamente dice: “le cose naturali sono soltanto immediate e una volta sola, mentre l’uomo come spirito si raddoppia, in quanto dapprima è come cosa naturale, ma poi del pari è tanto per sé”, ovvero l’uomo esiste di per sé come oggetto, ma nello stesso tempo è in grado di creare a sua volta altri oggetti, che non sono necessariamente oggetti artistici, ma che sono trasformazioni della natura. Non esistono in natura ma sono “oggettualizzazioni” di qualcosa, da cui prende il via la tensione progettuale, lo sviluppo incessante della progettazione e della produzione, il sistema delle “cose” che sempre più diventano protagoniste trasformandosi da “oggetti” a “soggetti”. È necessario comprendere che, purtroppo, la broken nature non è soltanto il risultato di un determinato sistema economico: appartiene, e proprio da questa consapevolezza è necessario riformare la pratica progettuale, alla natura dell’uomo e in modo particolare alla sua “autonomia creativa” che è nello stesso tempo la sua forza ma anche il suo limite. Inventare ex novo al di là di ogni limite, rispetto a tutti i modelli precedenti: una serie infinita di oggetti/prodotti che, pur partendo da un modello o da una necessità funzionale, che è sempre in prima istanza anche una necessità simbolica, progressivamente assumono una propria autonomia, allontanandosi dai linguaggi della natura, anzi trasformando spesse volte la natura come se fosse un artificio, ovvero intesa anch’essa come un prodotto dell’uomo. Da qui è necessario riflettere per tentare di ricomporre, se pur parzialmente, una natura già spezzata, una natura alienata perché appare a noi come sempre modificabile, mentre la condizione naturale possiede una propria autonomia “costruttiva” con le proprie leggi.

AC: Ancora una volta sottolinei con forza la centralità dell’uomo progettista, centralità che deriva dal pensarsi totalmente “autonomo” rispetto al contesto, come se fosse “l’invenzione pura” una sorta di forza della natura, che comunque agisce, come vediamo tutti i giorni, anche contro la stessa natura. Il design, ma, direi anche, tutte le arti applicate che hanno a che fare con il sistema dell’abitare e in generale si trovano in relazione con il mondo empirico, dove il tempo e lo spazio appaiono come variabili soggettive, mentre la natura sembra ritrarsi, in attesa di “reagire”, sembrano aver sposato, acriticamente, questo ruolo dell’uomo come “assoluto creatore” un dominus che vuole essere natura e artificio insieme. Dove risiede la ragione ultima di questa sorta di dominio sul mondo?

GD: Come dicevamo, la tendenza dell’uomo di assumere su di sé questa sorta di dominio sul mondo è sempre esistita, ma è soprattutto in questi ultimi decenni, con lo sviluppo delle nuove tecnologie, che assistiamo a fenomeni preoccupanti, a cui ho dedicato una serie di analisi. Questa tendenza è sempre da ricondurre a una condizione particolare dell’uomo di oggi: l’identificazione totalizzante con il concetto di “creare”, che si è esteso dalle arti tradizionali alle arti applicate che determinano lo sviluppo della società, dalle nostre case alle città che abitiamo, dai trasporti al posto di lavoro, dal modo in cui comunichiamo fino alla realizzazione di un uomo artificiale. Tutto il nostro environment è già totalmente trasformato dalla tecnologia. Queste trasformazioni, a parte gli immensi benefici materiali che hanno apportato all’umanità, costituiscono una totale diversificazione nelle condizioni di equilibrio tra uomo e natura, creando una serie di effetti negativi. L’horror pleni, ovvero l’assenza di un intervallo tra un fenomeno e l’altro, impedisce di declinare le differenze, per cui tutto appare omogeneo ed eguale a se stesso, da qui la moltiplicazione di oggetti inutili, seriali, che moltiplicano la complessità, a fronte invece dell’annuncio, ideologico di una semplificazione al servizio della natura dell’uomo.4 Oppure fatti che appaiono veri, ma non sono altro che fake news; in sostanza, una falsa conoscenza del mondo, per cui una telenovela è più vera della tragedia sotto casa.5 Anche in questo caso, la moltiplicazione dei linguaggi, dei sistemi di rappresentazione, ma anche il facile accesso a questo tipo di comunicazione e di rappresentazione che si sovrappone alla dimensione reale dell’esistenza, quasi sostituendola, provoca non solo problemi di ordine patologico, sul piano della coscienza di sé, ma soprattutto riempie i nostri spazi di una serie infinita di intermediazioni tra noi e il mondo, tra la natura e l’artificio, per cui è difficile orientare anche le nostre scelte.

AC: la ricerca di un equilibrio progettuale dove il design, ad esempio, sia espressione di un rapporto organico con la natura, ma anche con tutte quelle forze della natura che per ora osserviamo come fenomeni estranei alla cultura del progetto, mentre potrebbero rappresentare alcune esperienze nel segno dello sviluppo e al contempo nel rispetto di un nuovo equilibrio, è sempre stato un tema a te caro. Al centro credo che resti ancora vivo il lavoro di un grande filosofo, Husserl, soprattutto riletto e interpretato da un tuo caro amico, Enzo Paci – fondatore insieme a te, ad Augusto Morello, Gio Ponti, Marco Zanuso, nel 1954, del Compasso d’Oro, il premio più importante a livello internazionale, dedicato al design industriale – che scriveva nel 1967, a proposito del rapporto tra scienza, tecnologia e sviluppo produttivo: ”se la scienza e la tecnologia non ammettono altre realtà oltre quella delle cose fisicalistiche, se la scienza dimentica il cogito, l’uomo, e lo rende cosa fisicalistica, alienata, allora la scienza perde la propria fondazione che si trova nel cogito, dimenticando la propria funzione per gli uomini e il telos per l’umanità”.6 Il progetto contemporaneo è ancora in tempo a rimettere al centro questo tipo di telos, che è anche la ragione della conoscenza?

GD: certo che è possibile, e Paci aveva ragione, senza dimenticare però alcune cose. La prima, fare in modo che arte e attività progettuali comunichino tra loro, senza però sconfinamenti di campi, altrimenti la moltiplicazione degli oggetti sarà implacabile e infinita. Non dobbiamo mai perdere l’originalità di ogni nostra azione progettuale, evitando le inutili imitazioni e le repliche autoreferenziali. Moltiplicare è positivo, senza però perdere l’originalità che è insita nel fatto che la natura dell’uomo è quella di creare incessantemente. Non è possibile tornare indietro, come se fosse esistita una sorta di Eden del progetto, siamo nella storia e nella storia dobbiamo agire. Dobbiamo, quindi, per ottenere un miglioramento della situazione attuale, ”riscattare l’innaturale”, trasformare eventi artificiali in eventi naturali, o “naturalizzati”, attraverso un’azione di volontà e di conoscenza. Si tratta di considerare “natura” non più soltanto la natura allo stato selvaggio, ma soprattutto tutte queste nuove forme di natura meccanizzata, elettronicamente integrata, ”internettizzata”. Occorre che le costruzioni artificiali dell’uomo vengano progressivamente “rettificate”, subendo quel processo di naturalizzazione che solo può conferire loro una nuova valenza creativa e simbolica, tenendo presenti e sempre sott’occhio tutte le ricerche e le invenzioni rispetto ai nuovi materiali, ai nuovi processi produttivi che tengano conto sia del consumo dell’energia sia dello spreco delle risorse. Senza mai, comunque, rinunciare alla libertà creativa: più autonomia nel segno della conoscenza, meno eteronomia perché porta alla ripetizione e all’imitazione di ciò che già esiste. Avremo sempre più bisogno di “oggetti nuovi” che, pur avendo la loro ragione d’essere dentro la cultura materiale preesistente, siano in grado di parlare il linguaggio di un futuro concreto, riconoscibile e nello stesso capace di dialogare con l’autonomia conoscitiva e interpretativa che ogni persona possiede, indipendentemente dalla lingua, dalla religione, dal livello economico. Ogni persona è soggetto di libertà; questa è la sua fondamentale dimensione naturale; ricomporla progressivamente significa agire nel segno di una natura non più broken.

1 cfr. Gillo Dorfles, Artificio e natura, Einaudi, Torino 1968.

2 cfr. G. Dorfles, Nuovi riti nuovi miti, Einaudi, Torino 1965.

3 cfr. G.W.F Hegel, Estetica, Einaudi, Torino 1967.

4 cfr. G. Dorfles, Horror pleni, Castelvecchi, Roma 2008.

5 cfr. G. Dorfles, Fatti e fattoidi, Castelvecchi, Roma 1997.

6 cfr. Enzo Paci, Per un’interpretazione della natura materiale in Husserl, “Aut Aut”, 100/1967.