EDITOR’S NOTE: This text, penned by futurologist and co-founders of Studio Monnik Christiaan Fruneaux and Edwin Gardner, questions the viability of the anthropocentric culture and holds it responsible for the lack of introspective gaze that defines our age– the loss of the stars bearing witness to that. In the context of the XXII Triennale di Milano, Broken Nature, Fruneaux’s words complements the project presented by the Dutch pavilion, I See That I See What You Don’t See, curated by Angela Rui, Marina Otero Verzier, and Francien van Westrenen.

Whatever exists outside of humanity has disappeared from our anthropocentric culture – the loss of the stars bears witness to that. It is time to curtail our enlightenment; our introspective gaze is no longer working.

We have lost the nocturnal darkness. In 2016, the Light Pollution Science and Technology Institute created an atlas of the night sky, a ‘where can you still see the stars?’ map. The findings are remarkable. For example, 99 per cent of the residents of the United States of America and the European Union – with all those stars in their flags – live in places where it is now impossible to see the Milky Way. The culprit is, of course, light pollution. Our cities are too illuminated, and you need darkness to see the stars. In his book, The End of Night, Paul Bogard estimates that 80 per cent of the children now being born in the USA and the EU will never, in their entire lives, experience what it is like to read a book by starlight. Hidden behind the reflected light from countless lamps, the most impressive natural landscape we know of – a source of inspiration for art, mysticism, science and entire civilizations – will remain hidden from them forever.

A few years ago, I spent a few months working in Tokyo. I lived to the west of the centre, on the Chuo line. One day, I woke up with the panicky feeling that Tokyo had swallowed the world. That reality, from now on, consisted of an endless city from which nature had disappeared. That there was only a single interior, composed of concrete, plastic and asphalt. This feeling was so oppressive that I ran to the Chuo line, searching for the end of the city. According to the metro map – a huge plateful of colourful spaghetti – I should reach the end of the city at some point. Whatever happened, thank goodness. After two restless hours, during which I watched a relentless urban landscape passing by, I got out at the end station. A small stop in some suburb or another. In the distance, there was the suggestion of a green hill. I started walking towards it. After half an hour I reached a fence. This was to be the end of Tokyo. On one side of the fence was the largest urban conglomeration that has ever existed, where 37 million people live and work in an artificial interior. On the other side of the fence, there was a forest.

In his book Delirious New York, from 1978, Rem Koolhaas writes: “Manhattan as the product of an unformulated theory, Manhattanism, whose program – to exist in a world totally fabricated by man, i.e., to live inside fantasy – was so ambitious that to be realized, it could never be openly stated.” Manhattan as an artificial interior, created by our imagination. Nowadays, most people do indeed live in a world entirely created by Manhattanism.

Virtually everything in our environment is conceived, designed, made, transported, bought, used and claimed by ourselves – and so reflects ourselves in one way or another. Things ‘of themselves’ no longer have the right to exist; they can therefore simply be replaced or pushed away, just as the starry sky is squeezed out of view. For the simple reason that it was not invented, bought or hung up by anyone. Or claimed – because it is unlikely that a fee could be charged for looking at it.

In this insane inner world that can, not incorrectly, be called a psychotic delusion, we have lost the view of what lies beyond ourselves. We no longer call this phenomenon Manhattanism. Nowadays, that would be a much too local interpretation. We use the term Anthropocene, which means Manhattanism but then on a planetary scale. How can we look outside again? There is a cure for this cultural navel gazing. It is called the overview effect, and it is experienced by astronauts when they observe Earth from space. The overview effect is a sensation that is often described as a deep sense of connection with, and responsibility for, all life on Earth – and for the Earth itself. It seems to be an indelible experience to see our home from so far away, so fragile in the vast nothingness. Once you have been touched by the overview effect, you can never go back. As Wubbo Ockels showed on his deathbed, in his emotional plea for sustainability and peace.

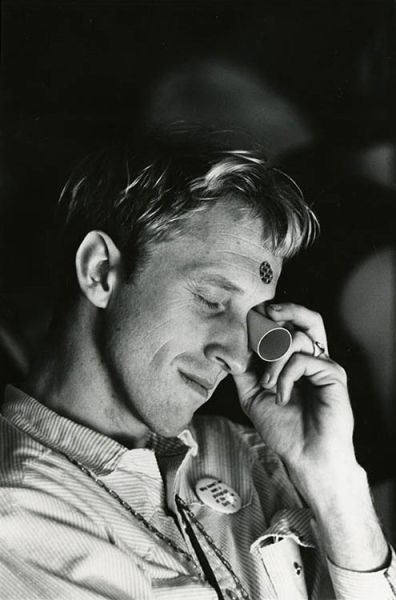

The overview effect is not reserved for astronauts. In the 1960s, cultural phenomenon Stewart Brand had his personal overview moment, after which he saw it as his mission to shake humanity awake. The hippie movement was in full swing, and Brand was one of its figureheads. He had just organized the Trips Festival and was contemplating his next step on the roof of a building in San Francisco, under the influence of LSD:

“So there I sat, wrapped in a blanket in the chill afternoon sun, trembling with cold and inchoate emotion, gazing at the San Francisco skyline, waiting for my vision. (…) I remembered that Buckminster Fuller had been harping on this at a recent lecture – that people perceived the Earth as flat and infinite, and that that was the root of all their misbehaviour. Now from my altitude of three stories and one hundred miles, I could see that it was curved, think it, and finally feel it.”

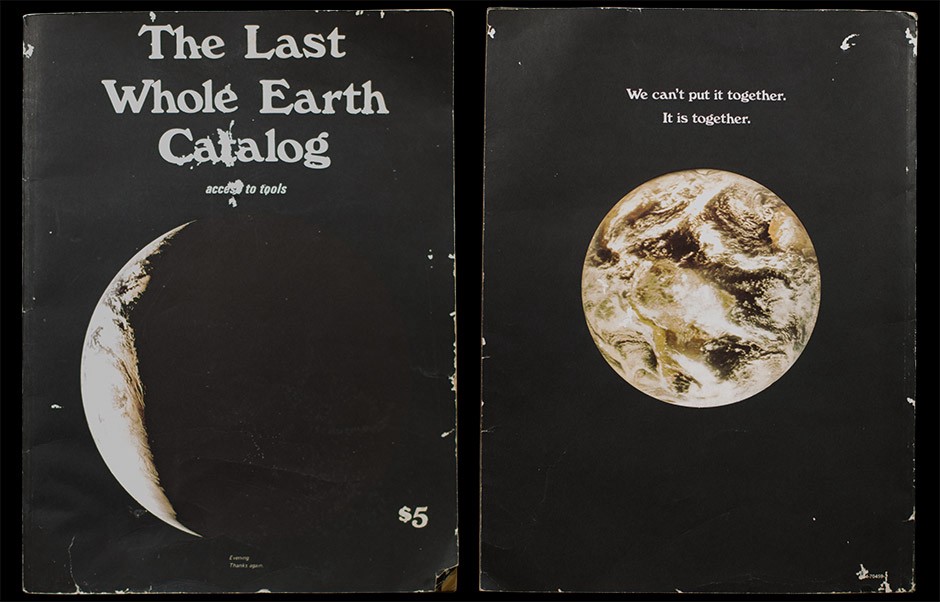

At that time, satellites were already floating around and Brand realized that there must be a photo of our planet seen from space. At that time, no one had ever seen a photograph of the entire Earth, so such an image could become a powerful symbol of the realization of its vulnerability, he thought. Brand started a campaign with the slogan: “Why haven’t we seen a picture of the whole Earth yet?” A year later, Nasa released a first photo of the entire globe (according to Nasa, one had nothing to do with the other.) Brand then started a magazine called The Whole Earth Catalog, and the Earth photo in question adorned its first cover. The magazine went like a bomb and The Whole Earth Catalog is now considered one of the most influential magazines ever published. It not only inspired the entire eco movement, but also a new generation of computer and internet pioneers.

Does this sound vague? Or is it reminiscent of a yoga class? At the University of Pennsylvania, they speak of a transcendent experience; an otherworldly encounter in which you coincide with your environment. But outside and inside can apparently coincide in two ways. Brand let the outside world flow in on the roof in San Francisco. Outside became inside. In Tokyo, I moved into an artificial interior in which there seemed to be no outside anymore. A world where inside had become outside. While space opened up for Brand and he felt himself coinciding with the world, I experienced a claustrophobic and isolated state of being. Manhattanism and the Anthropocene – two words for the inverse of the overview effect. The question is now, how can we make the overview effect a general experience, accessible to everyone? It would be difficult to send everyone into orbit for a few weeks.

There are plenty of arguments that politicians and policymakers can put forward as to why we should bring the starry sky back to our cities, without running the risk of having to go back to the drawing board with embarrassment. For example, light pollution is bad for public health. Our chronobiology is synchronized with light. Our chronobiology is therefore confused by the disappearance of the dark. This has an effect on our stress levels, which can have all sorts of other nasty physiological and psychological consequences. And this is all the more true for the ecosystems that surround us, because animals and plants cannot close the curtains at night. Moreover, it saves energy when we dim the lights or turn them off. And, lastly, we can hold up the starry sky as natural heritage. As we did with the Wadden Sea.

All good arguments, with demonstrable precedents that decision makers can fall back on. But as far as I am concerned, the best reason – which, like Manhattanism, cannot be stated openly – is to dim the ‘enlightenment’ (with both a small and a capital E) so that we can once again have a view of what lies outside ourselves. So that we can once again embrace the starry sky as a cosmic frame of reference. A daily reminder that there is something bigger than ourselves. That we have to take into account things that do not originate in ourselves – meaning, if we want to survive these times.

We live in a humanistic culture in which people and their interests are central to every consideration. This has brought us a lot but has not been a viable starting point for some time. We have to learn to live together with the life around us – which is now outside our narrow view – and to develop a post-humanistic view. But then we must first sense that our previous arrogance was somewhat out of place, that we do not represent much on a cosmic scale. This is frightening, but also empowering, just like the overview effect. We can achieve it by travelling to the stars and looking down, or simply by turning off the lights and looking up.