EDITOR’S NOTE: Into(x) the Wild, a project by designer Livia Stacchini, focuses on Rosignano Solvay (Tuscany, Italy), a place that in a 1999 report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) was deemed to be one of the 15 most polluted coastal sites on the Mediterranean Sea. Despite its reputation, the aesthetic appeal of Rosignano Solvay’s White Beaches (Spiagge Bianche) makes most people turn a blind eye towards the damaging effects of human activity on the environment. Into(x) the Wild was exhibited during Dutch Design Week 2018 in Eindhoven.

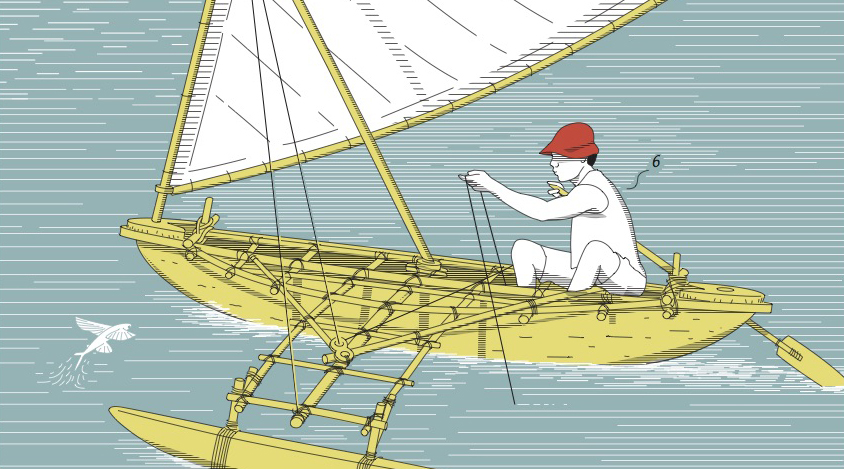

How can we define nature today? If humans are part of nature, should landscape alterations caused by human activity be considered a natural phenomenon? The purpose of the project, Into(x) the Wild, was to attempt an answer to these questions, and to rethink the relationship between humans and nature. The designer chose the small town of Rosignano Solvay as a case study. Rosignano is located on the Tuscan coast, some 25 km from Livorno, on the spot where, in 1914, the Belgian chemical company Solvay founded one of its biggest plants in Europe.[1] Strangely enough, the landscape of Rosignano Solvay is reminiscent of a paradisiac and exotic island getaway; indeed, it attracts many tourists, to the point of having been renamed the “Caribbean of Italy.” The factory produces Solvay’s main commodity––sodium carbonate, commonly known in Italy as Soda Solvay. For decades, the by-products of this production process were released into the sea, altering the surrounding environment [2] and giving it its notorious West Indian-like appearance. As a result, the landscape has become a by-product itself, a supplementary commodity produced by the factory in the form of a popular tourist attraction.

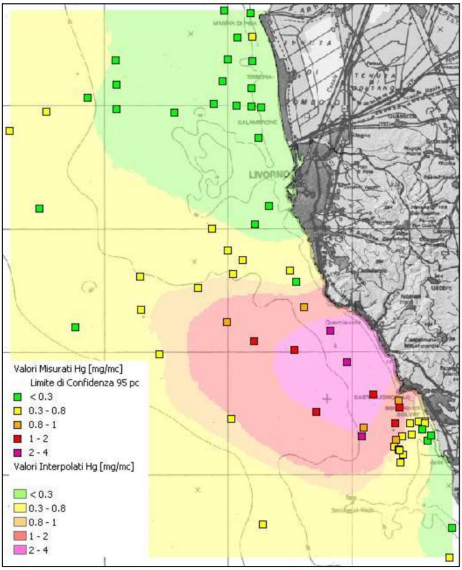

With its white beach and turquoise sea, Rosignano Solvay could really be a paradise. Unfortunately however, what lies behind the white sand and crystalline water is a manmade chemical transformation of the landscape due to the waste materials released by industrial activities. Some tourists do not know why the sand is so bleached, while others do; but the experience of vacationing in a beautiful place that looks like the tropics wins over any doubt or reservation. In reality, the sea and the seabed of Rosignano contain toxic chemical elements such as cadmium, nickel, chromium, lead, arsenic, and especially mercury, elements which have been released into the sea for the last few decades, up until 2010.[3] Solvay produces sodium carbonate by means of the so called “Solvay process,” which consists of chemical reactions between salt (brine), limestone, and ammonia—the end product being sodium carbonate, or soda, a cleaning detergent for interiors.[4] As the by-products of this manufacturing process, sodium carbonate, calcium chloride, and limestone are the main components of Rosignano’s whitened sand. Moreover, the waste materials resulting from sedimentation are making the coastal land expand, making this is the only area of the whole region where the coast is growing instead of being eroded by natural geological processes.[5] Some of the key points that informed the Into(x) the Wild project are paradoxes–between growing land and eroding soda; between cleaning the interior of buildings and polluting the exterior environment; between the macro scale of the landscape and the micro scale of one single crystal. Eventually, the project resulted in an installation comprising a series of experiments to grow soda and salt crystals. The goal was to shed light on the paradoxical impact of our obsession with hygiene, and to demonstrate how economic and social processes are shaping the contemporary landscape.

Video of the crystals installation at the Dutch Design Week 2018 in Eindhoven.

[1] Rosignano Solvay, Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2018.

[2] Spiagge Bianche (White Beaches), Atlas Obscura, accessed March 24, 2018.

[3] Gianni Lannes, Mercurio all’ultima spiaggia Su la Testa! (August 8, 2012), accessed April 14, 2018.

[4] Solvay process, Wikipedia, accessed January 26, 2018.

[5] Comune di Rosignano, Componente geologico tecnica ed idrogeologica, Carta Geomorfologica, map, scale 1:40,000, March 2002.

[6] ARPAT, Qualità delle acque marino costiere prospicienti lo scarico Solvay di Rosignano (2014), available at Issuu, accessed January 24, 2018.