Upon visiting Lapland earlier this year, chasing the northern lights, I never expected to become so utterly transfixed with the cultures, economies, and governmental policies surrounding, of all things . . . reindeer husbandry. Lapland (also known as Sápmi) stretches across the northernmost parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, above the arctic circle. A clever marketing ploy has nominated Rovaniemi, the capital of Finnish Lapland, the “Official Hometown of Santa Claus,” and claims that there are more reindeer living in the region than there are people. The indigenous people of Lapland, the Sámi, have been the caretakers of Lapland’s reindeer for hundreds of years, following the semi-domesticated herds as the animals move between seasonal grazing grounds, and building a culture intimately tied to herding traditions. Reindeer husbandry is both an economic livelihood and a way of life that is deeply rooted in the Sámi culture and tradition.

Contemporary reindeer husbandry is described to the average tourist visiting Lappish Finland as an idyllic coexistence between Sámi and Finns, where the Sámi maintain traditional ways of living among and raising reindeer with the support of a government invested in preserving their culture. Reindeer roam freely across state-owned or public land for most of the year. Should a Sámi’s reindeer go rogue and destroy a neighbor’s mailbox, the paliskunta—the local, cooperative reindeer-herding district—will pay for the damage rather than saddling the financial burden on an individual owner. Conversely, if a reindeer is hit by a car and killed, its owner is compensated by the government for their loss of potential profits. Furthermore, the Finnish government takes on the responsibility of determining the ecosystem’s carrying capacity of reindeer each year—herders may be required to cull reindeer to ensure that the population does not deplete the land’s resources to a greater degree than the land is sustainably able to support.

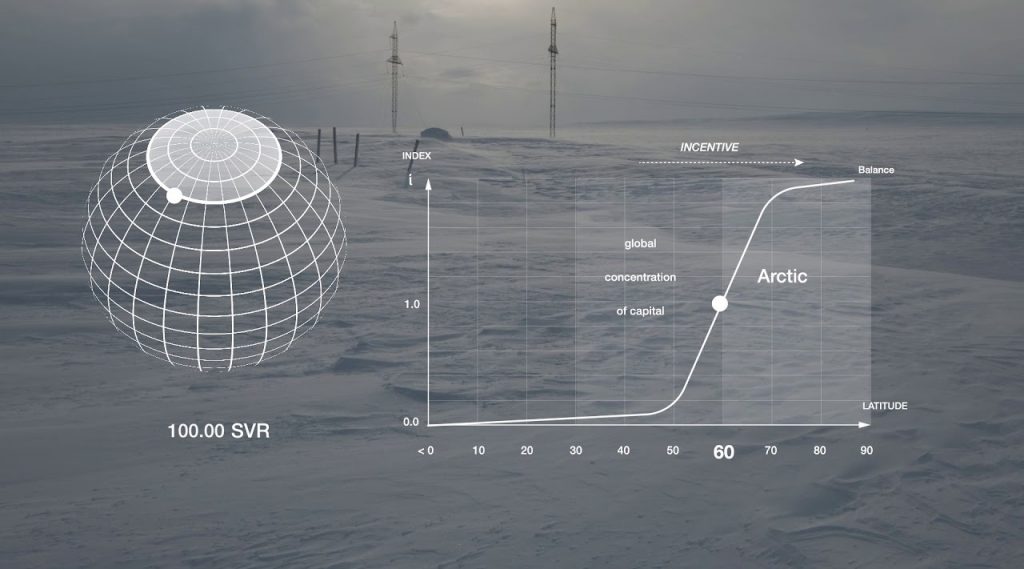

Despite the government taking meaningful steps to support indigenous peoples in the development of an industry rooted in traditional practices, and considering the complexities of preserving nature in its legislation, the system falls short when you consider the fact that Sámi are currently scattered across four different countries. Indeed, international borders have been closed to herders since the nineteenth century, and they are now obliged to remain within national frontiers, further fragmenting migration routes and herding pastures already threatened by industrialization and climate degradation. While Sámi maintain cultural autonomy protected by the Finnish Constitution, they do not have sovereignty of their own, nor decision-making authority outside of their involvement in reindeer husbandry. Moreover, consider limitations of how a government distills generations of Sámi ontology—continuously refined, adapted, and updated through daily experience—into legislation. Perhaps this requires a more nimble and qualitative approach than governmental policy may be able to provide. In this uneven power relationship between Sámi and Nordic governments, as well as the oversimplification of a cultural knowledge in attempting to assimilate and protect heritage through legislation, it is not surprising that problems arise. Regardless, it is intriguing to consider the possibility of an institution where multiple distinct ontologies can exist together productively and peacefully.

There are estimated to be somewhere between eighty and one hundred thousand Sámi people living across Sápmi. A small percentage of them remain actively involved in reindeer husbandry practices, either earning most of their income tending reindeer year round or, more commonly, receiving supplemental income from reindeer herding in addition to other revenue streams like fishing, agriculture, or tourism. While in Norway and Sweden Sámi maintain the exclusive right to reindeer husbandry, any citizen of the EU can own reindeer in Finland so long as the owner is approved by the paliskunta and remains a permanent resident of that locality. Most reindeer in Finland are part of smaller herds managed by a paliskunta and belong to members of these permanently settled populations, which earn money from several occupations. Though some nomadic Sámi communities continue to tend large herds of reindeer year round, the paliskunta is the method of reindeer herding most regulated and subsidized by the Finnish government.

The Finnish government’s motivation to begin regulating reindeer herding escalated after WWII in an attempt to manage the various interests of agricultural entities, infrastructure developers, and forestry groups. In the late 1940s, Finland was under pressure to pay war penalties while also taking advantage of new access to global markets. Logging forests in Finland became a top governmental priority, because it was seen as a way to pay debts and quite literally pave the way for roads and other developing infrastructure. Since reindeer need large swaths of pasture and grazing areas, and are migratory by nature, their resource needs were seen as an impediment to the country’s desire to industrialize.

Over the next several decades, reindeer husbandry developed into the system used today, regulated in Finland by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF). The MAF’s various divisions determine the maximum number of reindeer permitted in a given year (carrying capacity), the compensation given to an owner when an animal dies unexpectedly (for example, if killed by a predator or in a traffic accident), the subsidy rate paid per reindeer, as well as various other legislative regulations surrounding reindeer husbandry. The MAF also funds the Reindeer Herders Association, a group that consists of representatives from each of the fifty-six paliskunta who advocate for their needs pertaining to reindeer husbandry. That said, attempts by the government to develop, regulate, and codify reindeer herding along the same lines as other modern economies remain at odds with the timeworn practices, rich vocabularies, and ideologies built over generations of Sámi reindeer husbandry—a neat translation between the two does not always exist.

As a kid, I spent the summer months camping across the United States, visiting the country’s many national and state parks. The motto that reigns supreme is “take only pictures, leave only footprints.” Visitors are encouraged to observe, to learn, to enjoy, but never to participate. The saying implies that preservation is only possible if we admire nature from a distance, and leave the details to the experts. I was intrigued by the community-oriented spirit and pride that surrounds Sámi reindeer herding, and its connection to the environment. What might the United States look like if varied ontologies were given the power to voice their expertise and experience on human relationships to animals and nature? Would vast herds of buffalo still roam freely across North America, instead of being another species added to the list of endangered animals? And what of the hundreds of Native American tribes who have lost their lands and ways of life in the face of a dominating force?

We can design salmon ladders, wildlife crossings, and artificial reefs in perpetuity, but until the framework in which we live also changes, we will be perpetuating an imbalanced organization in which nature, animals, and even peoples are considered manipulatable, rather than interconnected entities with equal stake in the well-being of our shared communities.