Cristina Gabetti is a journalist and writer, an expert on sustainability and ecology, and much, much more. She is a peaceful warrior committed to raising awareness with present and future generations and to reconnecting us with nature, and, ultimately, with ourselves.

“If we could all stop for a moment during our busy days to take a big breath, look at the sky, a tree, a flower, a face, or a façade, we would allow ourselves to remember that we belong to this awesome planet. And that we love it. Caring is a simple but crucial step in building a more sustainable world,” she has written. In fact, for Cristina, sustainability is not only a list of goals agreed to by nations, companies, or organizations but a daily exercise that starts within. Her journey inward brought her to see how we live with different eyes. And her research has proved that it’s time to honor what we know and act accordingly. She began experimenting, curious to find eco solutions that felt right—without sacrifice and without blame.

Having found the experience inspiring and abundant, in 2008 she published her first book, Tentativi di eco-condotta (Attempts at Ecological Behavior), in which she presents a vast collection of conscious choices and brings in scientific data to prove that they make sense. The success of the book led to her weekly segment on Striscia la notizia, one of the most popular and long-running Italian TV comedy/current affairs shows. Her segment, Occhio allo Spreco (Eye on Waste), brought to a vast public success stories of individuals and companies that practice regenerative solutions in Italy. Five years ago, the segment became Occhio al Futuro (Eye on the Future), where she investigates how technologies can help us solve humanity’s grand challenges.

What struck me when I first met her is that she actually practices what she preaches, and consistency, especially when it comes to ecological behavior, is hard to find. Most of the objects in her house are restored or recycled. She tries to avoid disposable plastic, drinks purified tap water, and keeps old clothes that she refreshes with a touch of a few new things. Her motto is quality over quantity. Her studio is part of her house and overlooks a small garden. On a bookshelf of recycled cardboard are her favorite books on ecology, circular economy, and sustainable development. The heating was quite low (in fact, truthfully, I was a bit cold!). Cristina was wearing a vintage scarf and a big sweater. She pointed out that her cozy merino wool shoes have sugarcane soles. “My jeans are 15 years old. I bought them dark blue and love seeing them fade as I wear them. They also help me stay in shape as they don’t stretch,” she explains.

I began my interview, which turned out to be a long conversation, quoting early twentieth-century political economist Joseph Schumpeter. We shared perspectives on how human beings, and the world we live in, are constantly evolving, with the convergence of environmental and systemic crises and technologies developing exponentially. We are undergoing profound, rapid change, and the challenge is to outgrow the previous system and shift to a new paradigm.

Sara D’Agati: At which stage of evolution are we in now, as human beings and in our relationship with nature, and what are the scenarios we are creating for our future?

Cristina Gabetti: When I use the word “evolution,” I just mean a stage of development. I don’t use it in a Darwinian sense. We are now on the cusp of a tipping point. We have surpassed the capability of our ecosystem to regenerate. The deeper we look, the more serious and irreversible the situation becomes. As humans, we are extremely complex beings, trained in the past five centuries to separate what should work in harmony: mind, heart, and spirit. Maybe that’s why today there is such a big effort to be wholesome and mindful. We need to scale awareness in order for restorative solutions to become pervasive.

SD’A: The modern era has placed the accent on rationalism, it’s true. But the paradox is that although—in the western world at least—we are aware that our economies are not sustainable anymore and that we are severely endangering our present and our future, we seem unable to bring this knowledge into action. Why do you think it’s so difficult for people to feel a sense of urgency?

CG: People are not good at thinking systemically and backcasting. “Backcasting” means taking a much longer trajectory into account and looking back before you look forward, connecting the dots. Facts are facts, and they need to be taken into account, but many are so terrifying that people have a hard time bringing them to a level of feeling and digesting them. We’re all in our heads so much. The more I research the complexity of problems and the webs of solutions, the more I realize that choosing to be restorative is an act of caring. Carpe diem doesn’t mean taking as much as you can but, rather, being present.

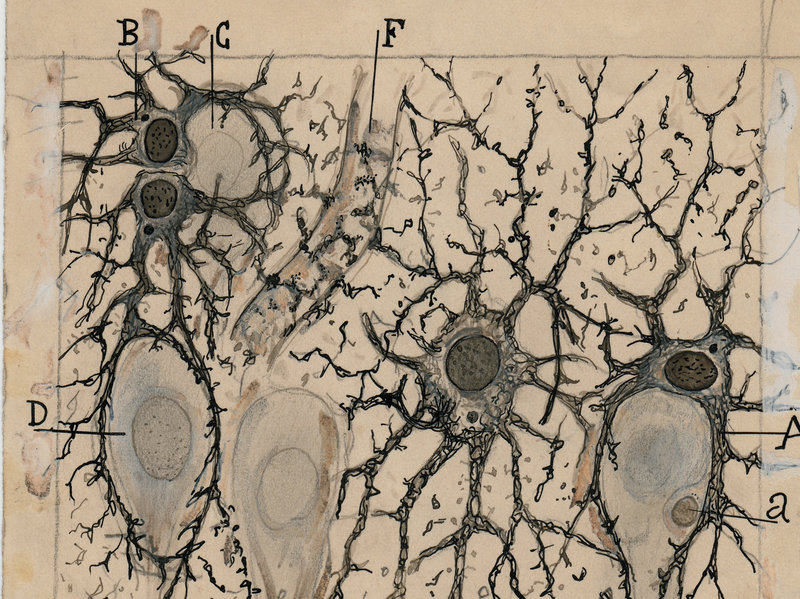

Awareness intended as “knowing what is going on” is certainly a starting point, but let’s take it to a deeper level. I’m trying to inspire people to reconnect with themselves and what they feel. In my experience it’s the best way to communicate and collaborate genuinely with others. One of my favorite discoveries in recent years is the mirror mechanism, and the work of neuroscientist Giacomo Rizzolatti. He proved, with his research team at the University of Parma, that we are all wired to feel with others. Empathy has a sound scientific base. In my last book, A passo leggero (Treading Softly), I explore empathy as a driver of positive change. I share stories of connections with others, with nature, and with myself in the hope to inspire people to activate their empathic drive. I support the validity of these spiritual exercises in a long conversation with Professor Rizzolatti. In the interview he explains how the mirror mechanism works and why in our society, it is often deactivated. But we can choose to turn it on. And he agrees that we need empathy more than ever before.

By restoring empathy, we can establish deeper connections. Nature is a great source of inspiration. By observing and contemplating, we can find answers to many questions, at a spiritual and practical level. We take for granted our biggest gifts: clean air, fresh water, healthy food, pristine nature. Many parts of the world are seriously compromised. Protecting the health of our ecosystems means protecting ourselves and society at large. This basic understanding needs to become relevant in the way we behave. It’s the underlying principle of the systemic change that needs to occur at all levels of society. When we act systemically, or holistically, priorities automatically change as the relations between cause and effect become evident.

SD’A: With your work, you are strongly committed to raising awareness about the future of our planet and the importance of being environmentally responsible. The peculiarity is that you do it in a very practical way, avoiding theoretical digressions and focusing on what everyone can do “to live better consuming less.” Starting with yourself, can you describe what would ideally be a sustainable day in a city, from the moment we wake up until we go to sleep?

CG: The first thing I do when I wake up is to rinse my face with lavender hydrolat, distilled from my plants, then I stretch my body and connect with my soul through meditation. This time for me is sacred. I am always mindful of the water that flows from the tap. I consider it a luxury. All soaps and detergents are eco-friendly. We keep the temperature in the house and in my studio at 19 degrees Celsius (66.2 degrees Fahrenheit) and wear warm clothes. This keeps the immune system active and the indoor air healthier. Compensating for the resources we consume has become a habit—a joyful one. We source our food locally, seasonally, and organically, and we buy fair-trade coffee and chocolate. We are not vegetarian, but we eat meat only twice a week that we get from farms that treat animals with respect. And I turn the lights off when I leave a room. Even in other people’s homes (embarrassing…).

SD’A: Often, the critique is that organic products are more expensive. Is living a sustainable life a privilege of the wealthy?

CG: No. Less is more. We’ve learned to not waste food and are creative with leftovers. We bring into our home things that last. We reupholstered our sofas from thirty years ago, and have restored antiques that have been in our families (my husband’s and mine) for many decades. I have come to appreciate the public transport system in Milan, and walking is the best way to connect with the world outside. Statistics say that many people who have more are less happy. It’s all in the attitude. As John Lennon said, life is one-third how we make it and two-thirds how we take it.

SD’A: One of the main points of investigation of Broken Nature is: how can designers, scientists, politicians, and scholars support citizens in taking constructive action on urgent issues related to natural and social environments. What is your view on that? What do you think can be done to facilitate the transition?

CG: Italy could be the most sustainable country in the world: we have six climate zones, our biodiversity is one of the richest in Europe, we have all sorts of landscapes—sea, mountains, plains, and rolling hills—more World Heritage sites than any other country, and the richest and most varied culinary tradition in the western world. The main obstacle I see is that we don’t think and act systemically. There needs to be more collaboration between different areas of knowledge. We lack a goal-driven mindset and are bogged down by bureaucracy. It’s often difficult to involve citizens in the political and economic process through mechanisms of open participation. The transition toward future-proof development is a global challenge that should be addressed at the super-national level by the international community. The UN and the European Union are actually creating laws that make sense. However, the problem is local implementation. Broken Nature comes at the right time, as local governments need to invest more in stimulating citizens’ participation in the decision-making process by communicating better and giving the public access to classified data in clear, understandable ways. Transparency is key.

SD’A: Even companies increasingly feel the pressure to communicate more transparently about their impact on the environment and on society. A clear example is the proliferation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) activities and claims. What do you think about the CSR trend? Is it only a way for companies to divert people’s attention, or is it a sign that something is changing in a positive direction?

CG: CSR is a very good idea, but companies need to go beyond face value, with viable actions and commitment. In my years of research I’ve learned to scratch under the surface and detect those who are for real versus those who see sustainability as a trend. Today, in order to create customer engagement, being transparent is vital. People want to know what they’re buying or using, but many don’t have the tools to understand the complexities. And on the other hand, citizens themselves must be willing to engage. It’s a team effort.

Big organizations and industries can have a very high impact on this process, for instance, by incorporating environmental costs in the price of products. It’s a way to say to consumers, “we’re in this together.” We’re all responsible but can become fully accountable only if we collaborate. Honest consumer engagement would have a great impact on society. While waiting for this to happen at a larger scale, we can promote bottom-up strategies by demanding more from industries, politicians, and policy makers, choosing what we buy coherently—there are some good companies out there—and giving ourselves incremental goals.

SD’A: In your long career focusing on environmental issues, you have listened to many stories. Is there a particular company that struck you positively for the way they approached the transition to a more sustainable practice?

CG: The process has just started, so it is understandable that not all companies have reached desirable standards when it comes to sustainability. But, being honest is definitely the right start. One entrepreneur that really struck me was Silvio Albini, of Albini Group, a textile company. He started our interview by stating that the textile industry is the second-worst carbon polluter. I have done hundreds of interviews, and I have never seen someone, particularly the CEO of a company, who spoke his heart in such a straightforward way. This gave tremendous power to the actions of his company, which are incremental over time: more organic cotton, less hazardous chemicals, wiser water consumption, and better agricultural practices. Following his internal revolution, the company saves 8 million kilowatts of electricity a year—equal to the electricity consumed annually by 2,700 households—and 46,000 cubic meters of water—equal to that contained in sixteen Olympic swimming pools.

This to say that there are people, even big players on the market, who understand where we are now and are willing to make a difference.

SD’A: Let’s turn to cities, for a moment. There is much talk today about smart cities, liveability indexes, and so on and so forth. According to the recently published ranking of Sole 24 Ore, Milan is the first smart city in Italy, and also the first city for liveability. However, Milan is also widely renowned for being one of the most polluted cities in Italy. How is that possible?

CG: Milan has improved enormously in the last few years. But I agree with you: How can a city be smart if it’s one of the most polluted? Does “smart” just mean having all our devices and appliances interconnected? In order to honor the meaning of the word, I feel that interconnected through technology is not enough. Being smart means using our humanness at its full potential, it means being aware of ourselves and of our role in the social and natural environments. I was really touched by Maurice Cox’s keynote at the second Broken Nature symposium, which took place at MoMA on January 14. As Director of Urban Planning and Development of the City of Detroit, he has restored public trust in the public administration. He brought a city that was dying back to life through a participative design process like none I’d ever heard of. He restored health and beauty, and equity and inclusion, by placing a big emphasis on the role of nature. I know how much I need nature to regenerate, and I’m not alone. Connectivity also allows people to work remotely, and my hope is that rural areas will not be abandoned. Nature might thrive without us, but we won’t without it.

SD’A: Among your many interests are bio-architecture and sustainable design, in the larger framework of the coexistence between humans and nature. Broken Nature is, indeed, a reflection on the increasing gap in the connection between humans and their natural environment, emphasizing design’s capability of repairing our species’ bonds with the world around and within us. In your opinion, where is the point of contact between us, nature, and design?

CG: Awareness is to me the point of contact. I am really fascinated by the role the tree in my garden plays. It’s a red sentinel that is feeding dozens of birds now—from parrots that escaped from a zoo in Milan that was closed two years ago and have since proliferated, to starlings and blackbirds. It’s beautiful to look at and it cleans the air we breathe. By manifesting its presence so generously, that tree gives me a sense of respect and belonging. I care for it, and it takes care of me. Perceiving circularity, which is the basic rule of nature, makes me feel alive. Circular design mimics the cycles of nature, and I hope we’ll see more and more of it. Everything we use should go back to nature harmlessly or be reused. I can’t wait to see Neri Oxman’s installation at the Triennale. She has taken this experimentation to its maximum potential.

SD’A: Can you point out a few examples of what you believe is a successful restorative design?

CG: The first that comes to mind is Daniela Ducato. I was thrilled to see she will be in the Triennale. She is restorative in every way: from her personality to her projects. She uses discarded sheep wool, production waste, to make a fiber that absorbs and digests petroleum in seawater. And she also uses waste from dairy farming to make paint. She is so ingenious that anything she transforms becomes a resource.

Another good example comes from the Human Sciences Department of the University of Turin, which houses the biggest collection of fungi, the largest “micoteca” in Italy. They are studying a variety of applications, from design to biotech, that use fungi to purify water and soil and to make a new class of pharmaceuticals. Fungi, which are classified as a kingdom, have enormous potential that is being explored in many research centers around the world. I’ve seen beautiful tiles harvested from fungi that return to nature at the end of their lifecycle.

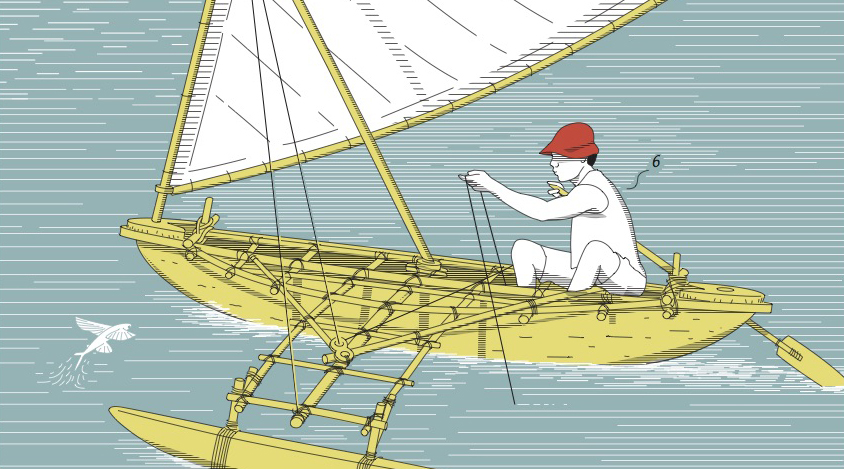

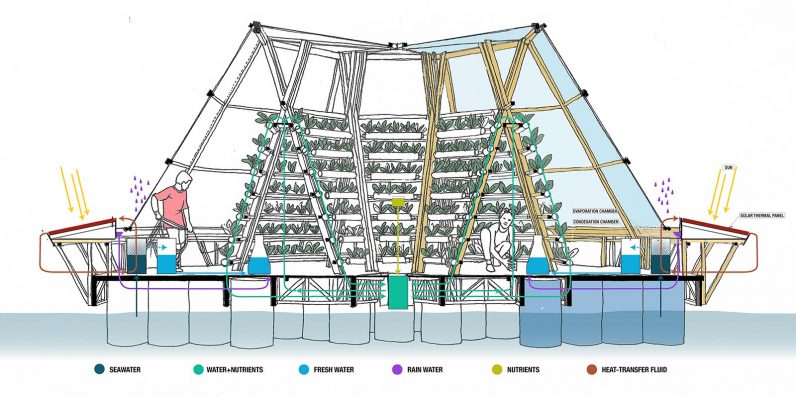

Then, of course, Stefano Mancuso, who has proved to the world that plants are intelligent. He will be curating the Nation of Plants at the XXII Triennale. I’m particularly passionate about his Jellyfish Barge, a floating greenhouse that purifies seawater using solar energy. He’s gained worldwide recognition for this modular, energy-neutral production unit but he has not succeeded in financing it because a head of lettuce would cost more than what we pay now at a supermarket. When the price of our food staples will incorporate the environmental costs of cheap labor, refrigerated transport, and distribution, people might see the opportunity. In a restorative design frame, communication and storytelling have a very important role. The design community can do a lot to facilitate the process.

SD’A: What about social innovation and social entrepreneurship? Do you think this could be the new point of contact between innovation, people’s rights, and sustainability? I often say that social innovation could be seen, in a way, as the new, progressive left, which the political system seems unable to express.

CG: Social entrepreneurship shouldn’t be labeled. It should be the only way to do business. Often people who are deeply affected by a crisis, be it environmental, social, or economic, come up with the best solutions to overcome them. I had the pleasure to work with Ashoka, the largest network of social entrepreneurs in the world, and saw firsthand how effective their scaling strategies are.

In general, now that environmental issues are making headlines everywhere, people are eager to find a way out, but they risk falling into the trap of quick fixes. A good example is the Ocean Cleanup. Boyan Slat raised 35 million dollars to fund his nets to collect plastic in the oceans. It was a dream that seduced many, including myself, but then I dug deeper and realized that it doesn’t make sense. Once the plastic is collected, what are we going to do with it? How much energy do we need to bring huge barges deep into the oceans and back to shore? We’re at a very interesting time, but we have to let go of the luxury of using a versatile, cheap substance, oil, to solve many needs. Identifying the best alternatives is challenging, but if we all agree that burning fossil fuels is in our worst interest, we’ll embrace the opportunities that are out there. I think we have it all, we just need to make the transition happen.

SD’A: I have one last question. Can you learn to care, if you don’t?

CG: Yes, we can train ourselves to care. It’s a matter of where we choose to put our attention and intention.