EDITOR’S NOTE: Design Without Designers is a research project conceived and developed by studio d-o-t-s during an art residency organized by the Moroccan association l’Atelier de l’Observatoire in the frame of its long-term project Musée Collectif de Casablanca. The project explores the creative powers of scarcity and resourcefulness by tapping into collective memory and anonymous design. It connects to several projects in Broken Nature—among them, Martino Gamper’s 100 Chairs in 100 Days and the Fixperts platform.

When architect Bernard Rudofsky first introduced to the world his selection of architectures without architects – on the occasion of the exhibition he curated at the MoMA of New York in 1964[1] – his main attempt was to reveal the “beauty” of what he called “non-pedigreed architecture.” Rudofsky claimed that “this architecture has long been dismissed as accidental, but today we should be able to recognize it as a result of a rare good sense in the handling of practical problems”.[2]

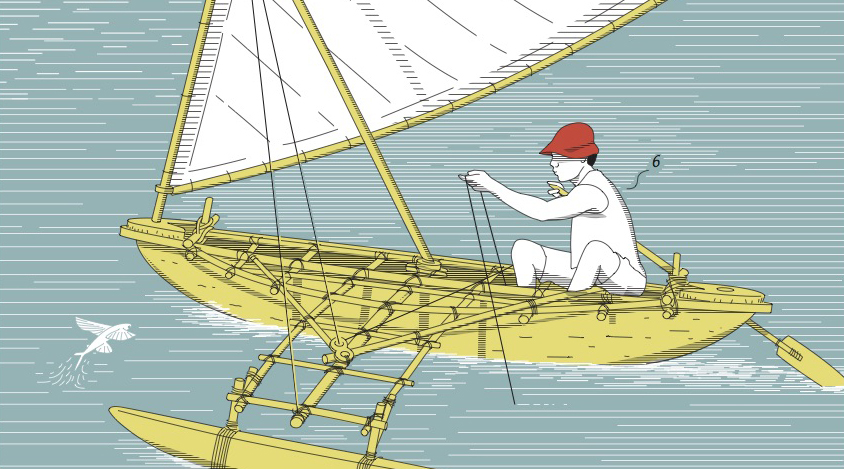

With a wink to the title chosen by Rudofsky for his highly debated exhibition, the project Design Without Designers wished to arouse the same attention in regards to some “bastard” design pieces – as German photographer Michael Wolf would call them[3] – found on the streets of Casablanca, Morocco. Self-started between 2014 and 2015 and finalized during a 3-week art residency organized by the Moroccan association l’Atelier de l’Observatoire in the frame of its long-term project Musée Collectif de Casablanca[4], our research also embraced Charles Darwin’s vision of adaptation as a creative, but unconscious, biological process that places organism modifications under natural laws – designed without a designer – in order to fit their habitat.

Described by French historian Alain Bourdon as a “Harlequin’s coat”[5], Casablanca is plural and composite. Field of many spontaneous experiences, the city has been witnessing an informal housing development since its early years. From the first shantytowns to the transformations that occurred within its social landscape during the French colonial period, many findings reveal how the built identity of the city was shaped by subsequent layers of appropriation by its various populations. As German researcher and curator Marion von Osten noted in an article published on e-flux, “as the users of the colonial modern infrastructures and landscapes, these dwellers and self-builders appropriate existing buildings, public spaces and territories to articulate personal needs and relieve the precariousness of their situation.” In the heart of the city, conventional constructions and informal structures still coexist today. However, while these appropriations have been widely studied at an architectural level, similar spontaneous adjustments happening at a smaller scale remain mostly unnoticed and unstudied.

Yet, torn between nostalgia and modernity, Morocco’s fastest growing city offers exciting perspectives on the creative powers of scarcity also from a product and furniture point of view. Absent from hip art galleries and far from the traditional vision of the country’s design vocabulary, which often coincides with the reinterpretation of its much-celebrated – but also highly folkloristic – craft heritage, a humble but vibrant creative language can be spotted in every corner of Casablanca. Composed of the waste of a booming consumerist society, DIY objects – chairs, portable ovens, street signs, planters, etc – stand like tangible witnesses of a need to turn the city into a place of one’s own, like an open-air communal living room.

Evoking the approach of Bernard Rudofsky, whose aim with his exhibition was to give credit not just to the architectures, but especially to the self-building capacities of the people producing them, Design Without Designers proposed to highlight the stories of a series of anonymous designers through the objects they created.

We decided to focus on chairs, a product typology prominently present in the city because of the many people – shoe shiners, car and parking keepers, cleaning ladies, plumbers and builders – that have the streets of Casablanca as their workplace and that need seats to perform their daily jobs. During our residency, we immersed ourselves in the city fabric and mapped the location of more than 40 chairs using an open web-mapping tool, interviewing the owners of 20 of them. The stories that we collected, which we compiled in a small catalogue illustrated by French illustrator LaoraLaora, speak to the ambiguous interconnections linking these people to the city where they were born or where they settled down in search for a better life. But they also narrate the daily struggle of their authors to earn their living and support their families, as well as the bond they developed with the chairs they carefully created using found elements that satisfied their needs for ergonomy and comfort. Intelligent and beautiful in their humbleness and roughness, with their aesthetics the seats unconsciously recall the work of established designers like Martino Gamper’s 100 Chairs in 100 Days project (2015), or the discoveries of other research projects such as The Museum of Other Things, a well-documented survey about “homemade and utilitarian items made by people not to sell, but for their own use”, that Russian engineer Vladimir Arkhipov[6] has been conducting in his home-country since 1994.

Met during our field investigation, the stool of Mr Abdelhadi – a 59 years old car keeper & cleaner and former sea soldier – particularly struck us with its refined design and bright appearance. “I have this chair since 2014 and, in the future, I would like to pass it over to my son if he decides to take my job when I retire. Along the years I modified it in order to better accommodate my needs; for instance, I would like to add two armrests and a sunshade at some point… If it disappears, everything stops, I cannot work anymore”, told us the man. It is this emotional charge that inspired us to run a 4-day workshop at the Ecole Supérieure des Beaux-Arts of Casablanca, during which we invited nine design students to develop an “ideal” chair for him. Based on Mr Abdelhadi’s specific requirements, the groups conceived and built four high chairs using ready-made objects and found materials. The final goal for them was to convince Mr Abdelhadi, the “client”, to exchange his beloved chair with one of theirs.[7]

As a conclusion to our residency, on January 5th 2019 we opened a small exhibition in which we showcased the findings of our research. The Ecole Supérieure des Beaux-Arts‘ gallery offered the perfect white-cube setting to decontextualise and celebrate 13 of the improvised chairs that we had collected during our stay. The light museum-like scenography that we conceived granted a real design-status to the objects, offering a new perspective on these anonymous objects and their authors. The chairs also created an interesting dialogue with the stools conceived by the students, as well as with the photographic work of Moroccan artist Rita Alaoui, whom we met during the residency and invited to participate. Entitled The eyes watching you, her on-going project portraits the chairs of car keepers and guardians as symbols of surveillance and control. Alaoui’s critical look at the role of these people in the Moroccan public space, whose jobs were created by the former king Hassan II as an unofficial way to check his people, enriched the show with an additional narrative layer.

Small in surface and easy to mount, Design Without Designers was thought as a traveling exhibition. After the first appearance in Casablanca (the show closed on January 13th) we are now working with the team of l’Atelier de l’Observatoire in order to show it in European museums.

[1]Architecture Without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-pedigreed Architecture, MoMA New York, 11 Nov. 1964 – 7 Feb. 1965.

[2] Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture Without Architects, A Short Introduction to Non-pedigreed Architecture, The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1964.

[3] Michael Wolf produced a series of books on the subject of informal seats and improvised sitting practices in the urban context. The first of which, Sitting in China, was published by Steidl in 2002.

[4] The Collective Museum is a citizen museum of the memory of the districts of Casablanca that offers a shared process of writing the history of the city by its inhabitants.

[5] Bourdon Alain, Didier Folléas, Casablanca : Fragments d’imaginaire, Institut français de Casablanca : Le Fennec, Casablanca, 1997

[6] Since the 1990s, Vladimir Arkhipov collects improvised objects spontaneously made during the USSR era. Carefully inventoried, the 1000+ objects make up The Museum of Other Things (www.otherthingsmuseum.com), a constantly evolving collection of designs that were born out of scarcity. A book about Archipov’s research, entitled Home-Made: Contemporary RussianFolk Artifacts, was also published by FUEL Design & Publishing in 2006.

[7] We met Mr Abdelhadi during one of our daily explorations across the streets of Casablanca. He was particularly inclined to share his story, and the one of his beloved chair, with us. Mr Abdelhadi visited the exhibition on the night of the opening and chose one of the chairs designed by the students to exchange it with his.